Introduction

Barcode Medication Administration (BCMA) systems are recognized as a pivotal health information technology, designed to minimize medication errors and bolster patient safety through precise verification processes.1 By automating checks via barcode scanning on medications and patient wristbands, BCMA aids nurses in confirming the ‘five rights’ of medication administration: right patient, right medication, right dose, right route, and right time.2 Driven by the imperative to mitigate the adverse effects of medication administration errors,3 healthcare institutions have strongly advocated for and implemented BCMA systems.4–7 Research has demonstrated BCMA’s effectiveness in significantly decreasing medication administration errors and reducing harm from serious errors.8 Furthermore, studies indicate improved patient identity verification rates following BCMA implementation.9 10

Despite being available for over two decades, hospitals have encountered challenges in seamlessly integrating and implementing BCMA within existing healthcare infrastructures,5 11–15 with numerous studies highlighting the critical role of the implementation process in determining BCMA’s overall success.12 13 Reports of increased workload and workflow disruptions due to BCMA use have led to the development of workarounds,7 12 14 16 17 such as pre-scanning medications onto carts.18 These workarounds, also termed policy deviations, can paradoxically introduce new error possibilities despite the technology’s intent.7 12 18

While prior research has identified workarounds and policy deviations associated with BCMA,7 12 18 limited investigation has been conducted to understand the underlying causes of these deviations and the contextual factors influencing their occurrence. A systematic review assessing BCMA’s impact on patient safety pinpointed human factors and technical issues as barriers to achieving intended scanning rates and patient safety benefits.1 Another review echoed these conclusions, emphasizing the need to explore whether deviations beyond the traditional five medication error types could significantly affect patient safety.19 Therefore, this study aimed to examine nurses’ interactions with BCMA technology and identify policy deviations as potentially unsafe practices, adopting a human factors approach.20 Specifically, the objectives were to: (1) gain comprehensive insight into nurses’ actual BCMA usage during medication rounds, (2) document the frequency and types of BCMA policy deviations during medication dispensing and administration, and (3) analyze the potential causes of these policy deviations in relation to the socio-technical elements of the work environment.

Methods

Overview

This study employed a concurrent triangulated, mixed-methods design, integrating structured observation (quantitative data) with field notes and nurses’ comments (qualitative data) concerning BCMA usage across two medical wards in a 700-bed Norwegian hospital. Structured observation, facilitated by a digital observational tool, quantified policy deviations. Field notes and nurse feedback provided context to the quantitative data, offering explanations and clues to the origins of policy deviations.

Theoretical Framework

The Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model16 20 provided the theoretical framework for this research. This model investigates the interrelationships between individuals, technology, and their work environment. It has been effectively applied in studies of medication administration technologies16 and broadly across healthcare settings.20 In this study, the SEIPS model was used to categorize integrated qualitative and quantitative data according to its five core elements20: (1) tasks, (2) organizational factors, (3) technology, (4) physical environment, and (5) individuals.

Setting

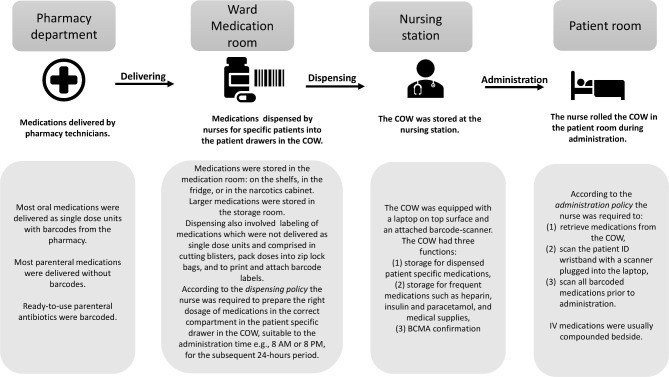

The hospital under study was the first in Norway to implement electronic Medication Administration Record (eMAR) and BCMA technology, rolled out over three years from 2017 to 2019. The eMAR and BCMA system used was Metavision, iMDsoft, incorporating digital medication records, barcode scanners, patient identification (ID) wristbands, single-dose medication units, and scanning protocols for dispensing and administration. The hospital utilized a decentralized, ward-based dispensing system. The processes for delivery, dispensing, and administration, along with relevant policy descriptions, are depicted in figure 1. Data collection occurred in two wards: a cardiac medical ward and a geriatric intensive care ward. Additional ward details and observation dates are available in online supplemental appendix 1.

Figure 1.

Description of the dispensing and administration process for BCMA, utilizing a computer on wheels (COW).

Supplementary data

bmjqs-2021-013223supp001.pdf (43KB, pdf)

Definitions

In this study, a policy deviation was defined as any act of dispensing or administering medication that did not comply with hospital policy. Task-related deviations included failures in tasks involving barcode scanning during dispensing and administration. Organizational policy deviations encompassed violations of hospital medication management policies, such as dispensing incorrect doses into patient drawers on the computer on wheels (COW). Technology-related factors were defined as issues with technological equipment (hardware and software) associated with BCMA. Environmental factors were elements of the physical environment impacting BCMA processes. Nurse-related factors pertained to the practices or comments of individual nurses.

Data Collection

Medication administration rounds were observed by one registered pharmacist and one fifth-year pharmacy student between October 2019 and January 2020. Observers contacted the assigned nurse on each ward before medication rounds, explained the study’s purpose, and secured written consent. Upon entering patient rooms, nurses briefly informed patients about the observer’s presence and study aims. Observers remained silent during observations to minimize bias.21 No patient-identifiable data was recorded. Observers were instructed to alert nurses if they identified a medication error with potential patient harm.

A digital observational tool (detailed below) was used to record quantitative data, with data consistency verified by the research team. Data were collected using handheld tablets and directly transmitted to a secure server. Following structured observations, observers documented qualitative field notes on the medication safety environment and any relevant nurse comments.

Data collection concluded when saturation was reached, determined by the research team’s assessment that further data collection would not yield new insights.22 The research team met regularly to review observation data and assess for saturation.

Development and Piloting of the Data Collection Tool

A digital observational tool was developed using secure web-based data survey software23 to gather data during medication administration. This tool was piloted for seven days by two observers, who monitored medication administration for 30 patients across two medical wards. While pilot data were excluded from the main study, the inter-professional research team discussed the pilot findings, evaluating each question in the observational tool for relevance to the research question and consistency with current evidence. Separate data collection tools were developed for oral and parenteral medications due to process variations (online supplemental appendices 2 and 3). The 28 questions in total (14 for each route) were aligned with hospital policy workflows, quantifying data on:

Supplementary data

bmjqs-2021-013223supp002.pdf (851.9KB, pdf)

Supplementary data

bmjqs-2021-013223supp003.pdf (823.6KB, pdf)

- Total medications, scannable and scanned medications, and scanned patient ID wristbands.

- Policy deviations related to dispensing, labeling, storage, or scanning.

- Technological problems with equipment or software.

- Storage practices for patients’ own medications.

- A free-text option for observer comments was included.

Analysis

Quantitative data from both observational tools were merged, and string data were converted to numerical values. Descriptive statistics using IBM SPSS V.25 were employed to analyze scanning rates and policy deviation frequencies. Qualitative data underwent inductive thematic analysis24 through an iterative process. Two researchers independently coded data, assigning utterances to emergent themes. The researchers then discussed theme fit and reached consensus. Following separate quantitative and qualitative data analyses, the two datasets were integrated using a triangulated approach.25 26 Key findings from both datasets were identified and compared to enhance validity and deepen understanding of policy deviations and their causes. Integrated findings were then categorized according to the five SEIPS model elements.20

Results

Observations included 44 nurses preparing and administering medications—29 during morning and 15 during evening rounds. A total of 884 medications (mean 4.2 per patient, range 0-14) were administered to 213 patients (table 1). Of these patients, 133 (62%) received only oral medications, 59 (28%) received both oral and parenteral, and 21 (10%) received only parenteral medications.

Table 1.

Observed Characteristics of Barcode Medication Administration

| Characteristics | Ward 1 | Ward 2 | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observation duration | 14 hours 35 min | 17 hours 48 min | 32 hours 23 min |

| Number of observed nurses | 22 (21 female; 1 male) | 22 female | 44 |

| Number of observed medication rounds | 18 (12 at 8:00; 6 at 20:00) | 20 (14 at 8:00; 6 at 20:00) | 38 |

| Total number of observed patients | 94 | 119 | 213 (100%) |

| Number of patients with scanned wristband | 85 | 85 | 170 (80%) |

| Total number of medications | 447 | 437 | 884 (100%) |

| Number of barcoded medications | 373 | 315 | 688 (78%) |

| Number of scanned medications | 319 | 306 | 625 (71%) |

Task-Related Policy Deviations

Data source: Observational tool

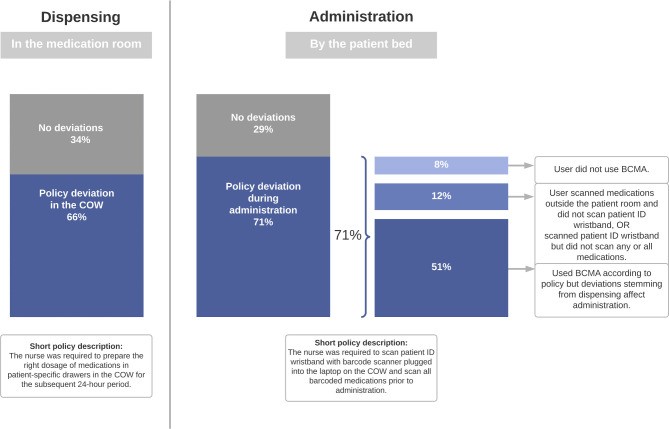

Data from the observational tool revealed how nurses utilized BCMA during dispensing and administration. Task-related policy deviations affected 140 patients (66%) during medication dispensing and 152 patients (71%) during medication administration, as illustrated in figure 2. During administration, three distinct variations in nurses’ BCMA use leading to deviations were identified: complete non-use of BCMA, partial BCMA use, and correct BCMA use where deviations still occurred.

Figure 2.

Task-related policy deviations observed during barcode medication administration (BCMA) using a computer on wheels (COW).

Organizational Policy Deviations

Data source: Observational tool, field notes, and nurse comments

Organizational deviations, defined as departures from medication management policies, included medication administration deviations such as not scanning 29% of medications and 20% of patient ID wristbands (table 1).

Ten types of policy deviations were identified during the dispensing process. The most common were medication not dispensed (n=80 patients), missing barcode label (n=70 patients), and wrong dose dispensed (n=30 patients). Dispensing deviations and their potential links to medication errors are detailed in table 2. Notably, three deviation types—wrong medication dispensed, wrong dose dispensed, and medication not dispensed and not administered—also qualify as actual medication errors, including medication omissions. These dispensing deviations in the COW often surfaced after nurses entered patient rooms, leading to prolonged and frequently interrupted administrations, and medication omissions for 25 patients. In 11 cases, eMAR scanning prevented the administration of wrongly dispensed medication. Observers intervened once when a nurse dispensed an incorrect (look-alike) medication from the medication room with the intent to administer it.

Table 2.

Organizational Policy Deviations in Barcode Medication Administration and Their Potential Links to Medication Errors

| Types of policy deviations* | N | Examples and descriptions | Potential medication errors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medication not dispensed; obtained and given during observation | 55 | Nurses did not verify dispensing omissions before starting administration rounds, despite knowing some medications (e.g., parenteral injectables) were not expected in the COW | Omission |

| Medication not dispensed; not given during observation† | 25 | Omission | |

| Barcode label missing | 70 | Dispensed tablets without barcode labels or primary packaging | Wrong medication, Wrong dose |

| Wrong dose dispensed† | 30 | Dispensed whole blister packs instead of single tablets (correct dose) | Wrong dose |

| Scanning failure | 26 | Barcodes on medications were unreadable by the scanner | Wrong medication, Wrong dose, Wrong route |

| Barcode label not attached | 13 | Barcode labels were in patient drawers but not affixed to medication; nurses stored expired labels to save time printing new ones | Wrong medication |

| Wrong medication dispensed† | 11 | Dispensed extended-release tablets instead of regular tablets; dispensed sound-alike medications (e.g., Lescol instead of Losec); dispensed 2g Cloxacillin IV bags instead of 1g; errors detected via eMAR scanning | Wrong medication |

| COW deviations due to recent eMAR changes | 7 | Antithrombotic medication dispensed in patient drawer, removed by nurse due to patient’s scheduled surgery | Contraindication, Wrong drug, Wrong route |

| Medication placed in wrong compartment in drawer | 5 | Morning medication dispensed in evening compartment of patient drawer | Wrong medication, Omission or wrong time |

| Wrong room number on patient drawer | 3 | Room number on patient drawer not updated after patient room change | Wrong patient |

| Wrong label attached | 1 | ‘Metoprolol’ label affixed to generic substitute Bloxazoc (metoprolol) unit dose; detected after scanning failure | Wrong medication, Wrong dose |

| Patients’ own medication stored in patient room | 24 | 96% deviation rate observed for patients’ own medications (24 of 25 total) | Wrong dose, Wrong medication |

*Deviation counts refer to one deviation type per patient, even if multiple instances of the same deviation occurred for one patient.

†Deviations also classified as actual medication errors.

COW, computer on wheels; eMAR, electronic Medication Administration Record.

Deviations from policies regarding storage of patients’ own medications (home-brought) were also observed. Policy dictated that these medications should be stored in the COW or medication room. A 96% deviation rate from this policy was recorded (table 2). Patients’ own medications were not integrated into BCMA, and were neither barcoded nor scanned.

Technology-Related Factors

Data source: Observational tool and field notes

Technology-related factors, identified through the observational tool, were implicated in 38 observations (18%). These included low laptop battery in 28 observations (13%), system freezing in seven observations (3%), malfunctioning barcode scanners in two observations, and scanner unavailability in one observation (online supplemental appendix 4). Software issues included slow response times and the need for repeated clicks after each medication scan. Nurses expressed frustration with the extensive clicking required using the laptop mousepad for eMAR navigation. The size of the COW was also cited as slowing administration and contributing to deviations.

Supplementary data

bmjqs-2021-013223supp004.pdf (40.9KB, pdf)

Environmental Factors

Data source: Observational tool, field notes, and nurse comments

Medication rooms were located at a distance from nursing stations and patient rooms. Nurses frequently moved back and forth to medication rooms during administration rounds to correct COW deviations. Undersized patient drawers, unable to accommodate all patient medications, also disrupted BCMA workflow. Additionally, work surfaces on COWs and nursing stations were often cluttered with single-dose units from previous administrations or incorrectly dispensed medications.

Nurse-Related Factors

Data source: Observational tool, field notes, and nurse comments

Several nurses admitted to infrequent daily use of barcode scanning equipment. In busy ward conditions, BCMA was often bypassed due to perceived slowdowns in medication administration. However, nurses who routinely used BCMA valued its automated verification, confirming correct patient-medication matches.

Probable Causes of BCMA Policy Deviations

Probable causes of BCMA deviations and their data sources are summarized in table 3. Task-related deviations, such as failure to scan medications during administration, often stemmed from dispensed medications not being scanned initially. A non-streamlined administration workflow resulted from mismatches with required administration tasks. Organizational deviation causes included unclear or poorly communicated policies, lack of policy awareness among staff, or policy incompatibility with existing workflows. Even with clear policies, deviations occurred; for example, despite policies stating only prescribed doses should be dispensed, whole blister packs were sometimes found in COWs.

Table 3.

Probable Causes of Barcode Medication Administration Policy Deviations According to SEIPS Categories

| Probable cause | Example from observation/description | Data source |

|---|---|---|

| Tasks related | ||

| Scanning discarded during dispensing | Medications dispensed without eMAR scanning failed to scan during administration | Observational tool |

| Workflow not adopted to required tasks during administration | Nurses frequently returned to medication rooms for undispensed medications, disrupting workflow and potentially impacting patient safety | Observational tool, Nurses’ comments |

| Suboptimal task performance | Voluminous medications (infusion bags, inhalers, eye drops) routinely not scanned during dispensing, retrieved during administration | Observational tool, Nurses’ comments |

| Organizational | ||

| Dispensing practices not adopted to nurse’s workload, normalizing deviations | Manual medication labeling during ward dispensing challenging without workarounds | Observational tool |

| Non-standardized dispensing process resulted in frequent deviations | Medications not barcode labeled, scanning failures, wrong dose/medication dispensed, missing medications, wrong labels | Observational tool |

| Unclear procedures or unassigned tasks | Inconsistent practices across wards regarding updating dispensed medications in COW due to recent eMAR changes | Observational tool, Nurses’ comments, Field notes |

| Poor routines/unfollowed routines for updating room numbers on patient drawers | Patient drawer room numbers mismatched patient rooms (patient drawers identified by room number for medication identification) | Observational tool |

| Lack of awareness of hospital policies | Patients’ own medications stored in patient rooms, violating policy requiring COW or medication room storage | Observational tool |

| Technology | ||

| Poor charging routines or non-compliance | Laptops frequently had low battery at start or during administration | Observational tool |

| eMAR usability issues | Slow eMAR response, excessive clicking needed post-medication scan | Field notes |

| Non-wireless scanners limited patient ID scanning | Medications scanned before patient room entry, administered with COW in hallway, patient ID wristbands not scanned | Field notes |

| Suboptimal COW design | Nurses avoided bringing bulky COWs for single medications; cumbersome COW design hindered workflow of patient room entry during rounds; COW medication storage for all patients, risky without scanning | Field notes, Nurses’ comments |

| Environmental | ||

| Medication room location affects task efficiency and administration time | Distant medication rooms from nursing stations/patient rooms slowed administration, led to nursing station storage of medications to avoid frequent trips | Observational tool, Field notes |

| Patient drawer size inadequate for proper BCMA use | Small patient drawers caused dispensing omissions, as only small oral medications/ampoules fitted, voluminous medications retrieved during administration | Observational tool, Field notes, Nurses’ comments |

| Non-specific medication storage policy | Random single-unit doses stored on nursing station desks/COWs, used if medications missing during administration; unsafe practice due to potential mix-ups | Field notes |

| Nurse related | ||

| Non-standardized dispensing allows variations | Performance variations among nurses, dispensing inconsistencies for same nurse | Observational tool, Field notes, Nurses’ comments |

| BCMA slower than manual verification—user dissatisfaction | Nurses completely bypassed BCMA during rounds; admitted to infrequent BCMA use, using it during observation | Observational tool, Field notes, Nurses’ comments |

BCMA, barcode medication administration; COW, computer on wheels; eMAR, electronic Medication Administration Record.

Technology-related deviation causes included inadequate charging routines, non-mobile scanners tethered to laptops, and software usability problems. The bulky COW design and non-wireless scanners hindered bedside patient ID wristband scanning. Undersized patient drawers also contributed to dispensing omissions due to insufficient storage capacity. Nurse-related deviations stemmed from BCMA process slowness, leading to scanning avoidance or technology bypass. These factors collectively compromised patient safety during medication dispensing and administration.

Discussion

This study revealed policy deviations impacting 60% of patients during dispensing and 70% during medication administration. Causes were attributed to complex dispensing processes, slow or cumbersome BCMA procedures, suboptimal technology design, and vaguely defined policies. In a busy environment, nurses found it challenging to consistently adhere to policies with suboptimal tools, leading to the normalization of deviations.

Despite these system imperfections, our findings indicate that medication and ID wristband scanning, when implemented, offered patient safety benefits by preventing wrong medication administration in 5% of patients.

Inconsistent dispensed dose delivery led to variations in COW medication dispensing. Patterson et al. 27 noted that BCMA enhances anticipation of actions and error detection. However, in our study, nurses could not assume dispensed medications were correct, necessitating manual dose re-verification before administration, undermining BCMA’s purpose.

Scanning rates in our study—71% for medications, 91% for scannable doses, and 80% for patient ID wristbands—fall below the 95% target standard for medication and patient scanning.28 A similar observational study in a UK hospital by Barakat and Franklin reported higher medication scanning rates of 83%, scannable doses at 95%, and patient verification at 100%.29 Despite a smaller sample size, their study’s similar ward-stock dispensing process and BCMA technology design make rate comparisons relevant.

A national Norwegian medication error study in hospitals without BCMA found 70% of errors occurred during administration.3 Many of these errors, such as wrong dose, patient, and medication, could be mitigated by BCMA implementation. However, even with accurate technology use, hospitals may not fully realize BCMA’s patient safety benefits, and unintended consequences can arise from technology implementation,18 as our findings demonstrate. In this study, intended technology use occurred in only half of administrations. Deviations frequently began in dispensing, including undispensed medications, wrong medication/dose dispensing, leading to further deviations even with correct BCMA use during administration.

Functional hardware is crucial for BCMA’s error-preventive effect. Recurring issues with uncharged laptops and scanner borrowing across wards were noted, but technology design issues were more significant. Bulky COWs and non-wireless scanners limited staff efficiency, potentially explaining the 20% patient ID wristband non-scanning rate. Others have also cited medication cart size as hindering BCMA efficiency.4 18 An observational study found nurses perceived manual patient identity confirmation as quicker than maneuvering large medication carts into patient rooms.27

Distant medication rooms indirectly compromised patient safety as time spent retrieving missing COW medications contributed to medication omissions. Undersized COW patient drawers also directly conflicted with safety, making dispensing omissions unavoidable for larger medications like eyedrops, inhalers, or syringes. Environmental factors have been shown to affect medication safety in other studies.30

Nurses in our study also reported BCMA prolonged administration times. Compared to settings with automated dispensing cabinets18 or pharmacy-operated dispensing,12 nurses in our study had more dispensing tasks (packaging, labeling, patient drawer dispensing), likely explaining the high dispensing deviation rates.

This study highlights variability in nurses’ BCMA use, ranging from complete bypass to partial and full compliance. This variability largely stems from doses lacking barcodes and policies allowing excessive workflow variations. Barakat and Franklin found BCMA reduced variability in medication administration.29 Safety culture differences may explain some of this contrast; in our study, inconsistent BCMA use may burden workflow rather than enhance safety. Lyons et al. 31 described similar performance variability with other medication technologies, suggesting adaptive behavior can compensate for system weaknesses but also raise concerns about unsatisfactory outcomes.

Implications

This study, conducted in a real-world BCMA setting, offers implications for technology implementation and improvement strategies.

- Hospitals should conduct pre-implementation risk assessments of policies to make institution-specific decisions on technology-workflow integration.

- Increasing the number of scannable medications could improve scanning rates. Pharmaceutical industry barcoding on primary packaging32 could reduce nurse and pharmacy workload and standardize ward dispensing.

- Ward-based medication dispensing, linked to higher error rates than unit-dose systems,33 should be evaluated for safety and efficiency.

- Technology redesign, such as replacing bulky COWs with lightweight carts and mobile eMAR devices, could improve nurse experience and mitigate current system downsides.

- Greater attention to BCMA usability and functionality is needed; lack of override logs and scanning stats in the observed system limits technology use monitoring.

- Ongoing assessments of BCMA use are vital, as policy and technology changes will introduce new deviations.16 Periodic medication round observations13 34 offer insights into technology use in context, and end-user involvement in improvement suggestions is crucial.

- Sharing BCMA practice learnings among hospitals with similar systems is important for knowledge improvement, implementation, and staff motivation.

Strengths and Limitations

The mixed-method approach provided detailed insights into nurses’ BCMA use and the context of deviations. Combining qualitative and quantitative data identified deviation frequencies and probable causes. The observational tool detected ‘normal’ deviations (e.g., wrong dose dispensing) often missed by incident reports and chart reviews.35 While prior studies show BCMA reduces error rates,4 5 7 8 identified policy deviations in our study suggest workarounds stemming from system flaws create latent conditions for serious errors. However, focusing on policy deviations rather than direct medication errors is a limitation, as it doesn’t directly measure BCMA’s patient safety impact.

Observer differences in data collection or local policy interpretation are potential limitations. Observers underwent thorough training in observational techniques36–38 and were familiarized with local policies to minimize this. The observer effect, where nurse behavior may be consciously or unconsciously modified,39 is also a consideration. Nurses were aware of being observed, and any behavioral change would likely be towards better BCMA compliance. Some nurses indicated observation-driven technology use. However, dispensing findings were less affected as dispensing occurred before observation periods, typically by previous shift nurses.

This study focused on eMAR paired with BCMA in a hospital with traditional ward-based dispensing by nurses. Generalizability to organizations using pharmacy-operated or automated dispensing may be limited. However, hospitals using ward-based dispensing can benefit from these findings, as research on BCMA use in ward-based dispensing is scarce.

Conclusion

This study offers in-depth understanding of BCMA use in clinical settings. Policy deviations were found in over half of observations, including non-scanning of patients/medications, dispensing omissions, and wrong dose dispensing. Variability in nurses’ BCMA use was also evident. Deviations were caused by unclear policies, policies hindering BCMA use (including labor-intensive dispensing), and technology design issues. Findings suggest work system reassessment and workflow adaptation are needed. Deviations are expected with technology implementation in complex systems. Analyzing policy deviations in practice is crucial for identifying and addressing system weaknesses to fully realize BCMA’s patient safety benefits.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to the nursing staff for their participation. They also acknowledge contributions from staff at the Southern and Eastern Norway Pharmaceutical Trust and the Department of Information and Communication Technology at the hospital.

Footnotes

Contributors: AM and AGG conceptualized the presented idea. KT, LM, and AGG contributed to planning and supervision. AM led data collection, analysis, and manuscript writing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study received internal funding.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: Supplemental content provided by the authors has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have undergone peer review. Any opinions or recommendations are solely those of the authors and not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims liability for reliance on this content. For translated material, BMJ does not warrant accuracy or reliability and is not responsible for errors or omissions arising from translation or adaptation.

Data availability statement

Data is not available. De-identified data from the observational tool or field notes is unavailable due to participant agreements not allowing broad sharing.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the institutional data protection board.

References

[References list from original article, maintaining original numbering]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

bmjqs-2021-013223supp001.pdf (43KB, pdf)

Supplementary data

bmjqs-2021-013223supp002.pdf (851.9KB, pdf)

Supplementary data

bmjqs-2021-013223supp003.pdf (823.6KB, pdf)

Supplementary data

bmjqs-2021-013223supp004.pdf (40.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data is not available. De-identified data from the observational tool or field notes is unavailable due to participant agreements not allowing broad sharing.