Introduction

In the fast-paced environment of modern healthcare, ensuring patient safety is paramount. Medication errors, particularly those involving incorrect patient identification or drug administration, pose significant risks. Health Care Barcode Scanning technology has emerged as a crucial tool to mitigate these risks, especially within medication administration processes. Barcode Medication Administration (BCMA) systems, which utilize health care barcode scanning, are increasingly adopted globally, often integrated with electronic prescribing and medication administration (ePMA) systems, to enhance accuracy and reduce errors. This technology mandates scanning a patient’s barcode and medication barcodes to verify their compatibility before a dose is administered. While the patient safety benefits of BCMA are widely recognized, including a reduction in medication administration errors and improved patient identification, the impact on nursing workflow remains an area of ongoing investigation. This article delves into the effects of health care barcode scanning on nursing activities and workflow, providing insights into its practical implications in hospital settings.

The implementation of health care barcode scanning in medication administration is reported to yield numerous patient safety advantages. Studies have shown a significant decrease in both the occurrence and severity of medication administration errors through the use of BCMA systems. One notable study in the UK demonstrated a dramatic increase in the verification of patient identity when BCMA was employed. A comprehensive international review further supports these findings, concluding that health care barcode scanning technology holds substantial potential for error reduction. However, it also emphasizes the importance of addressing human factors to fully maximize its benefits. A key concern is the potential disruption of nurses’ workflow by BCMA systems, which could lead to workarounds that undermine the system’s effectiveness. These workarounds can include bypassing essential scanning steps, such as transferring a patient’s barcode to a more easily scannable object. Despite these concerns, the actual impact of health care barcode scanning on the daily activities and workflow of nurses has remained relatively underexplored.

Direct observation studies have offered some insights, suggesting that the time nurses spend on medication administration tasks may remain consistent or even decrease with BCMA, while time allocated to direct patient care can remain stable or increase. However, many of these studies compare BCMA (integrated with ePMA) against traditional paper-based medication administration systems. In many hospitals, ePMA systems are already in place when BCMA is introduced. Furthermore, nurses’ perceptions of health care barcode scanning systems are varied. Some nurses report an increase in the time spent on medication administration, suggesting that BCMA reduces time available for direct patient care. Conversely, others argue that the additional time spent is a worthwhile investment in ensuring accurate medication verification. Reports from nurses often cite BCMA as slowing down their workflow, partly due to technological challenges and operational difficulties. These conflicting reports underscore the need for more research in this area, acknowledging that the context of implementation significantly influences outcomes. Therefore, the objective of this article is to evaluate the impact of health care barcode scanning, specifically BCMA when integrated with an existing ePMA system, on nursing workflow in a UK hospital setting. The aim is to compare matched BCMA and non-BCMA wards across several key indicators:

- Duration of drug administration rounds

- Timeliness of medication dose administration

- Active identification of patients by nurses

- Active verification of medication by nurses (BCMA only)

- Nurse movement patterns within the ward

Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

This study was conducted in a large acute hospital in London, UK, across two surgical wards. Data were gathered on a gastrointestinal surgery ward that had not yet implemented BCMA and a vascular surgery ward, identical in layout, four days post-BCMA implementation. Each ward had 24 beds, divided into four bays and four side rooms.

During medication rounds, nurses administered medications from ward stock, patient-specific dispensed medications, and patients’ own medications brought from home. Patient-specific and home medications were typically stored at the bedside, while ward stock was in the medication room or lockable cabinets on Computers on Wheels (COWs). In the non-BCMA ward, about half of the ten COWs had medication cabinets, accessible to all staff, which sometimes were not available during drug rounds. In contrast, the BCMA ward had five COWs with larger, dedicated medication cabinets for drug rounds and five COWs without cabinets for general use. Nurses used the ePMA system on COWs to view scheduled doses and record administrations. Before BCMA, each dose required an electronic signature post-administration. Drug rounds were scheduled at 8 am, 12 pm, 2 pm, 6 pm, and 10 pm, with most medications timed accordingly. Each nurse was responsible for a five-bed bay and possibly a side room.

The hospital used Cerner Millennium for its ePMA and BCMA systems. Post-BCMA implementation, nurses used barcode scanners tethered to designated COWs during medication rounds. After accessing a patient’s medication record, the system prompted nurses to scan the patient’s wristband for identity verification. The patient’s medication list appeared, and upon scanning each medication barcode, the system validated the dose. Nurses could then electronically sign to confirm administration of all medications for that patient, instead of signing each dose individually. The system issued a warning if patient or medication barcodes mismatched, allowing nurses to correct errors or override with a justification.

2.2. Study Design and Data Collection

This comparative study used direct observation to collect data during 8 am drug rounds. Data collection spanned ten consecutive weekdays in November 2019 on the non-BCMA ward and ten weekdays in December 2019 on the BCMA ward. Bay “H” was randomly selected for daily observation. Nurses responsible for this bay during each drug round were asked to consent to observation by a pharmacy student, who aimed to be as unobtrusive as possible. The study was approved as a service evaluation, and NHS ethics approval was not required. Outcome measures and data collection methods are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Outcome measures with method for data collection. COW = Computer on wheels; BCMA = Barcode medication administration.

| Outcome Measure | Method |

|---|---|

| Drug administration round duration | Time from opening the electronic record on the COW for the first patient to the time when the last medication dose was recorded as administered. |

| Timeliness of medication administration | Scheduled and actual administration times for each observed dose, excluding ‘when required’ medications. |

| Active positive patient identification activity | Non-BCMA ward: nurse confirmation of two patient identifiers (wristband check or verbal confirmation). BCMA ward: barcode scan of wristband or confirmation of two identifiers. |

| Active positive medication dose verification activity | BCMA ward only: recording whether medication barcode was scanned for each dose and reasons for not scanning. |

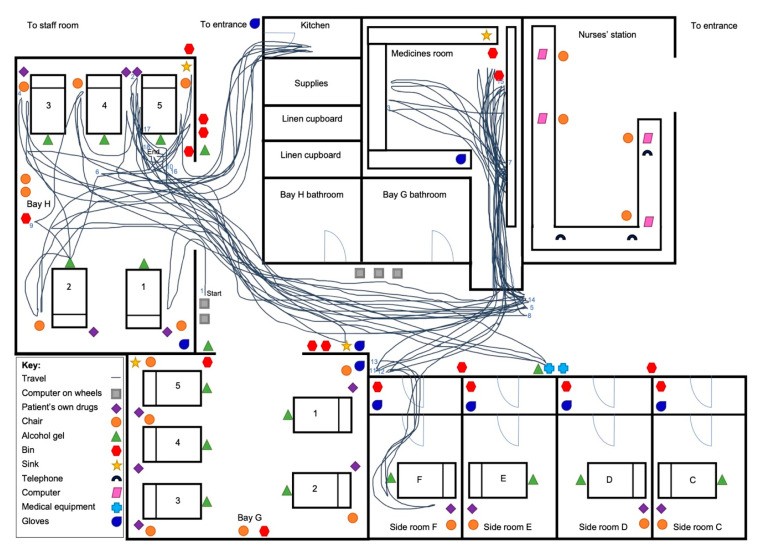

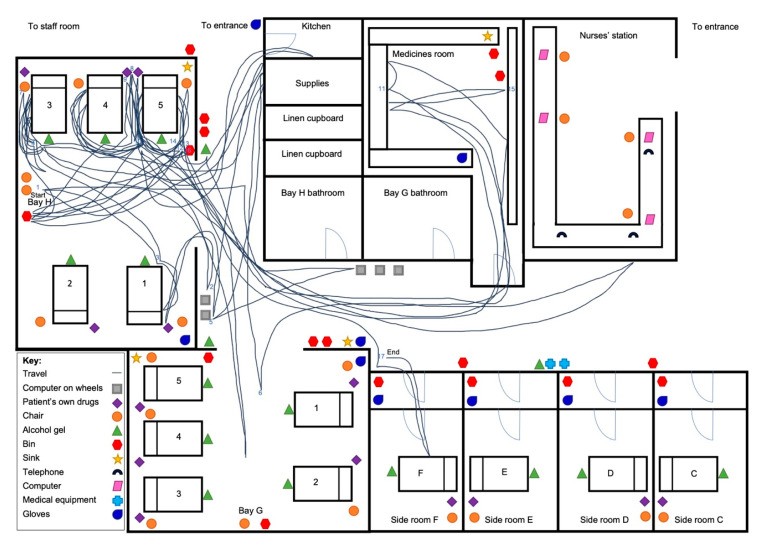

Spaghetti diagrams were used on eight drug rounds per ward to map nurse walking patterns. These diagrams charted the nurse’s movement from the start to the end of the drug round, overlaid on a ward floorplan. The first two days on each ward were used to create the floorplan.

Quantitative data were entered into Excel. Mean drug round duration was the primary outcome measure, analyzed using an unpaired t-test to assess statistical significance. Secondary analyses included mean time per patient and per dose. Timeliness was assessed by the mean time difference between scheduled and administered times. The percentage of patients identified was calculated and compared using a chi-square test. On the BCMA ward, the percentage of verified medication doses was also calculated. Spaghetti diagrams were visually analyzed to identify differences in walking patterns and activities.

3. Results

Observations included ten drug rounds on each ward. The number of patients receiving medication varied from three to six per round, with mean administered doses of 17 (range 7–25) on the non-BCMA ward and 29 (range 21–38) on the BCMA ward. Seven nurses were observed on the non-BCMA ward and eight on the BCMA ward.

3.1. Drug Administration Round Duration

The mean drug round duration was 67.8 minutes (range 27–98 min) on the non-BCMA ward and 68.0 minutes (range 48–99 min) on the BCMA ward (p = 0.98; t-test), indicating no significant difference. However, there was considerable variability in drug round duration, particularly on the non-BCMA ward, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Figure 1: Comparison of drug round duration over time between the non-BCMA ward and the BCMA ward, illustrating the consistency of duration despite the introduction of Barcode Medication Administration.

The mean time per patient was 14.1 minutes (range 9.0–19.6 min) on the non-BCMA ward and 16.0 minutes (range 11.6–20.0 min) on the BCMA ward (p = 0.17; t-test). The mean time per dose was significantly lower on the BCMA ward at 2.3 minutes (range 1.8–3.2 min) compared to 4.2 minutes (range 3.3–5.5 min) on the non-BCMA ward (p < 0.001; t-test).

3.2. Timeliness of Medication Administration

On the non-BCMA ward, 165 of 185 scheduled doses (89%) were administered, while on the BCMA ward, 294 of 363 doses (81%) were administered. Unadministered doses were due to patient refusal, dose review needs, or unavailability. The mean time difference between scheduled and administered times was 60.3 minutes on the non-BCMA ward and 67.5 minutes on the BCMA ward. Medication administration was statistically more timely on the non-BCMA ward (p = 0.007; t-test). Notably, drug rounds on the BCMA ward often started later, with seven of ten starting after 8:30 am, compared to only one on the non-BCMA ward.

3.3. Active Positive Patient Identification

On the non-BCMA ward, 35 of 47 patients (74%) had their identification checked before medication administration. In contrast, on the BCMA ward, all 43 patients (100%) received identification checks, a significant increase with BCMA (p = 0.001; chi-square test). On the non-BCMA ward, all positive identifications were manual wristband checks. On the BCMA ward, BCMA scanning was used for patient identification in 40 cases (93%), with manual confirmation in 13 cases (30%). Side room medication administration (7% of cases) involved scanning a barcode sticker from patient notes instead of wristbands, supplemented by manual wristband checks due to infection control policies prohibiting COWs in side rooms.

3.4. Active Positive Medication Verification

On the BCMA ward, 255 of 294 administered doses (87%) had scannable barcodes. Unscannable medications included repackaged patient-owned drugs and unpackaged insulin pens. Some items like nutritional supplements lacked BCMA system identification, requiring manual signing. Of 294 doses, 243 (83%) were scanned, representing 95% of scannable doses. Only 12 potentially scannable doses were not scanned, 11 of which were subcutaneous enoxaparin doses prepared in the medicines room. For these, nurses often left the box, which could have been scanned, in the medicines room.

BCMA system warnings occurred in 14 cases (6% of scanned doses). One error (0.4% of scanned doses) involved incorrect formulation selection, corrected by the nurse. The remaining 13 warnings included issues like unidentified barcodes, variable doses requiring manual entry, half-tablet doses flagged as overdoses, and early administration overrides. Nurses took corrective actions in all warning cases, either manually amending records or providing override justifications.

3.5. Observation of Nurse Walking Pattern around the Ward and General Activity

Spaghetti diagrams illustrated distinct walking patterns between wards. Figure 2 shows a non-BCMA ward diagram with extensive movement between patient beds and the medicines room, typical of four out of eight diagrams. The other four showed less ward movement. Conversely, BCMA ward diagrams (Figure 3) consistently showed reduced movement to areas like the medicines room, with most walking occurring between patient beds.

Figure 2.

Figure 2: Spaghetti diagram depicting a nurse’s walking pattern on a non-BCMA ward during a drug round, highlighting frequent trips to the medicines room.

Figure 3.

Figure 3: Spaghetti diagram illustrating a nurse’s walking pattern on a BCMA ward, showing reduced movement to the medicines room and more streamlined workflow between patient beds.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

This study indicates that implementing health care barcode scanning for medication administration, specifically BCMA, does not significantly alter the overall duration of drug rounds. However, the interpretation is nuanced due to a higher number of doses administered per patient on the BCMA ward. The reduced time per dose in the BCMA setting suggests an increased efficiency, enabling nurses to administer more medications within a comparable timeframe. While the data suggest a decrease in the timeliness of medication administration with BCMA, this may be attributed to later drug round start times on the BCMA ward. If start times were consistent, the efficiency gains from BCMA could potentially enhance medication administration timeliness. BCMA streamlines medication administration, harmonizing processes and diminishing the need for nurses to frequently visit the medicines room for medication preparation and retrieval.

The implementation of health care barcode scanning led to a 100% patient identification check rate, as the system mandates scanning a patient barcode before medication administration. However, the observed workaround of scanning barcode stickers from patient notes for side room patients, practiced by multiple nurses, raises concerns. This practice, while seemingly pragmatic, introduces a potential risk of patient misidentification and could undermine the intended safety benefits of BCMA.

The high medication scan rate is a positive indicator of BCMA system adherence among nurses during medication administration. However, the under-scanning of enoxaparin boxes by most nurses suggests a gap in either training or awareness regarding the scan capabilities for all medications, or potentially practical reasons for not scanning. Beyond enhancing patient identification, health care barcode scanning demonstrated its direct patient safety impact by alerting a nurse to an incorrect medication formulation during scanning, preventing a potential medication error.

4.2. Comparison to Previous Research

This study uniquely examines the impact of health care barcode scanning as an addition to an existing ePMA system, differing from previous studies that often compared BCMA against paper-based systems, thus limiting direct comparisons. Our findings diverge from a US study that reported increased total medication administration time with BCMA. However, that study attributed the increase to more time spent on direct patient care during drug rounds, with medication administration time itself not increasing. Our study did not measure nursing activity categories, preventing a direct comparison of BCMA’s impact on different nursing tasks. The workaround we observed, involving scanning barcode stickers instead of patient wristbands, aligns with previous reports, indicating this could be a common issue across various healthcare settings.

4.3. Interpretations and Implications for Practice

Health care barcode scanning in medication administration appears to standardize the process, promoting the use of designated COW medicine cabinets and streamlining workflow. It also offers the potential to reduce medication documentation time by enabling batch signing for all doses per patient. Despite these efficiencies, the total drug round duration remained unchanged in our study. This could be due to the higher volume of doses administered on the BCMA ward and the time taken for scanning, particularly patient wristbands, which sometimes appeared cumbersome with the COW setup. As health care barcode scanning systems become more prevalent, these findings underscore the need for user-centric design improvements, such as wireless scanning devices that are also suitable for use in isolation rooms.

The improved rates of patient identification and medication verification are significant for patient safety. However, to maximize medication verification, expanding the identifiable medication database and enhancing nurse education on system capabilities are essential. A longer adjustment period and additional training could address these areas. There is also a potential risk of complacency, as some observations suggest nurses might assume BCMA systems negate the need for manual checks like expiry date verification.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of Research

As one of the few studies investigating the impact of health care barcode scanning on nursing workflow, this research provides a valuable foundation for future studies. A key strength is the consistency in data collection and workflow assessments, maintained by a single observer. Direct observation also mitigates biases associated with self-reporting.

However, the study’s limitations include the use of two different wards. Ideally, a pre- and post-implementation study on the same ward would have been preferable, but logistical constraints due to BCMA implementation delays prevented this. While the chosen wards were similar, differences such as drug round start times and COW models, and the significant variation in doses administered, may have introduced bias. Other unobserved practice differences cannot be excluded. Data collection shortly post-BCMA implementation on the BCMA ward means staff familiarity with the system might not have been fully developed. The study’s size is also relatively small, and the generalizability of findings to other institutions with different practices and BCMA systems is uncertain. Finally, the observer effect might have influenced nurse behavior, though this would have been consistent across both wards.

4.5. Implications for Future Research

Future research should focus on longitudinal studies within the same wards to directly compare pre- and post-BCMA workflow, and observe drug rounds at various times. Larger sample sizes and longer data collection periods, preferably months after BCMA implementation, would better capture routine practice after the initial adjustment phase. Employing time-motion or work sampling methods to quantify time allocation across nursing activities would further enrich our understanding.

5. Conclusions

This study suggests that health care barcode scanning, specifically BCMA, does not negatively impact the time nurses spend on medication administration. While our data indicated less timely medication administration with BCMA, this finding should be interpreted cautiously and requires further investigation, ideally in pre- and post-BCMA implementation studies on the same wards. Overall, BCMA appears to standardize medication administration workflows. The notable increase in active patient identification and high rate of medication verification highlight the potential of health care barcode scanning to significantly enhance patient safety in medication administration processes.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the nursing staff on both wards for their participation in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.D.F.; methodology, S.B. and B.D.F.; formal analysis, S.B. and B.D.F.; investigation, S.B.; data curation, S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.; writing—review and editing, B.D.F.; supervision, B.D.F.; project administration, S.B. and B.D.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no specific funding. B.D.F is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Imperial Patient Safety Translational Research Centre and the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Healthcare Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance at Imperial College London, in partnership with Public Health England (PHE). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, PHE, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.