Introduction

Accurate assessment of wounds is paramount in healthcare, guiding treatment strategies and predicting patient outcomes. Burn injuries, a particularly severe form of wound, necessitate precise and timely evaluation to determine the extent and depth of tissue damage. While clinical judgment remains the standard, its accuracy, especially among non-specialists, is limited. This has spurred the development and evaluation of advanced diagnostic instruments to augment clinical assessments and improve wound care. In the context of wound care facilities, such as those in Northern NJ, the adoption of innovative technologies is crucial for delivering optimal patient care. This article delves into the landscape of imaging technologies for wound assessment, with a particular focus on multispectral imaging (MSI) and its potential to revolutionize evaluation practices in burn and broader wound care. We will evaluate the advancements in this field, examining the principles, clinical relevance, and translational potential of various instruments, highlighting MSI as a promising tool for enhancing wound evaluation and ultimately, patient care in regions like Northern NJ and across the globe.

The Critical Need for Enhanced Wound Assessment

Clinical assessment of burn wounds, the cornerstone of initial diagnosis, relies heavily on the expertise of the clinician. Burn specialists achieve an accuracy rate of 70–80% in determining burn depth.1 However, in settings outside specialized burn centers, where initial assessments are often performed by non-experts, accuracy significantly drops to approximately 60% for burn depth and a concerning 51% for burn size estimations.1,2 This disparity underscores a critical gap in accurate wound evaluation, particularly in initial care settings and geographically diverse regions like Northern NJ, where access to burn specialists might be limited.

To bridge this gap and enhance the precision of wound evaluation, a multitude of imaging devices have emerged as valuable adjuncts. These instruments offer objective, quantitative data on wound characteristics, potentially surpassing the limitations of subjective clinical judgment. Despite the availability and proven potential of these technologies, routine adoption in burn centers, including those serving Northern NJ, remains surprisingly limited. This review aims to address the recent progress in wound imaging technologies, focusing on the evaluation of multispectral imaging (MSI) as a particularly impactful advancement for burn wound assessment and its relevance to wound care practices in areas like Northern NJ.

Translational Relevance and Clinical Impact of Imaging Technologies

The majority of wound imaging methods, including MSI, are uniquely positioned for seamless integration into clinical practice due to their non-invasive nature. Operating predominantly within the optical range of the electromagnetic spectrum and often requiring minimal or no patient contact, these technologies present minimal risk in human subject studies and routine clinical use. This non-invasiveness is particularly advantageous in wound care, minimizing patient discomfort and the risk of infection during evaluation.

This review emphasizes the translational pathway for MSI in burn diagnosis, outlining a conceptual machine learning algorithm model as an example of the necessary steps for clinical development. By focusing on clinically available devices and emerging techniques, we aim to provide a comprehensive evaluation of current and future tools for wound assessment. This is especially relevant for clinicians in Northern NJ and similar regions seeking to enhance their wound care capabilities with cutting-edge diagnostic instruments.

Background: Understanding Burn Pathophysiology and the Need for Objective Evaluation

Burn Triage and the Burn Care Workflow

Successful translation of imaging technologies into routine clinical practice hinges not only on diagnostic accuracy but also on seamless integration into the clinical environment and workflow. The slow adoption of technology in burn assessment highlights that accuracy alone is insufficient for widespread acceptance.3 Evaluation of new instruments must consider user-friendliness, adaptability to diverse clinical settings (emergency rooms, operating rooms, tank rooms), and ease of use by personnel with varying levels of expertise, including nurses and surgeons in busy centers or smaller facilities in Northern NJ.

In many instances, burn victims initially present to hospitals lacking specialized burn care units. In these settings, healthcare providers, often with limited burn experience, must rapidly estimate the total body surface area (%TBSA) of the burn using techniques like the Wallace Rule-of-9s and assess burn depth. The documented inaccuracies in %TBSA overestimation (50% of assessments) and burn depth misjudgment (40% of assessments) by inexperienced personnel 1,2 emphasize the critical need for user-friendly, reliable diagnostic instruments readily available in diverse healthcare settings, including community hospitals in Northern NJ, to improve initial wound evaluation.

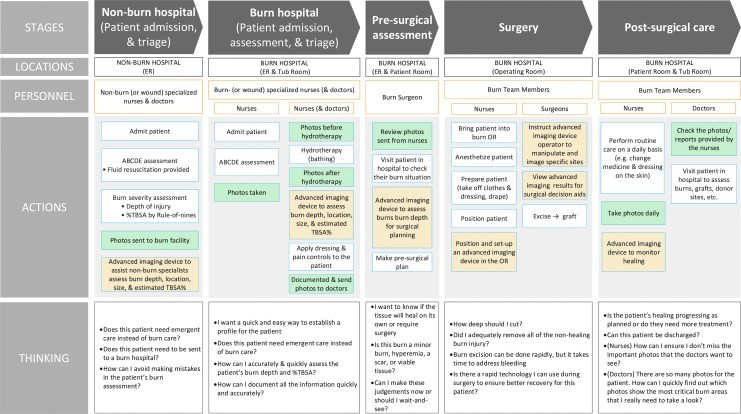

To contextualize the role of imaging technologies, we present a Burn Care Workflow (Fig. 1) that outlines the information needs at each stage of burn care. This workflow identifies key assessment points where imaging technologies can significantly contribute, including: initial burn depth and %TBSA determination, monitoring wound infection and healing progression, guiding pre- and intraoperative debridement decisions, and continuous perfusion monitoring in circumferential burns. For healthcare providers in Northern NJ, understanding this workflow and the available evaluation tools is crucial for optimizing burn patient management.

Figure 1.

Summary of the workflow of a typical burn patient across the spectrum of care, highlighting stages, personnel, actions, and considerations. Green boxes indicate typical photography points, while orange boxes suggest advanced imaging device utilization for burn depth or %TBSA determination. TBSA, total body surface area.

Pathophysiology of Burn Injuries

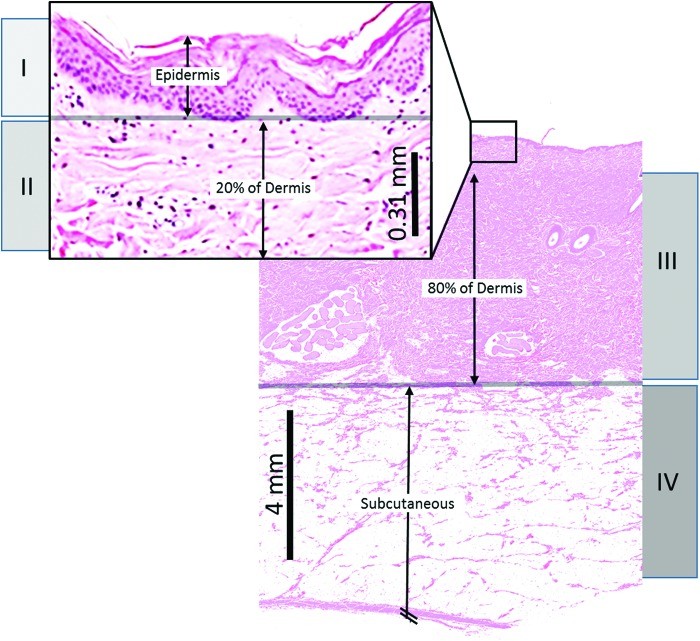

Effective wound imaging relies on the ability to detect specific pathological features of burn injuries and surrounding tissues. A thorough understanding of burn pathophysiology is therefore essential for evaluation of imaging instruments. Burn pathology is characterized by two primary aspects: the depth of tissue injury and the physiological responses in the tissue zones surrounding the injury. Burn depth classifications, corresponding to cellular destruction levels, are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Illustration depicting skin depths of destroyed cells for different burn degrees: (I) superficial, (II) shallow partial thickness, (III) deep partial thickness, and (IV) full thickness. Histology from porcine burn experiments is shown, noting slightly thicker skin than humans.

Burn Severity and Zones of Injury

Burn severity ranges from superficial (first-degree) burns affecting the epidermis to full-thickness (third-degree) burns extending into subcutaneous tissue and muscle. Partial-thickness (second-degree) burns are further categorized into shallow and deep, based on dermal involvement. Accurate determination of burn severity is crucial for appropriate treatment planning, and objective evaluation tools can significantly aid in this process.

Burn zones, concentric areas surrounding the burn site (zone of coagulation, stasis, and hyperemia), reflect the cellular response to injury. The zone of stasis, characterized by ischemic effects, is vulnerable to burn progression, where superficial partial-thickness burns can evolve into deeper injuries over 24–48 hours. Understanding these zones is important for interpreting imaging data and evaluating the effectiveness of different imaging modalities in detecting burn severity and progression. Table 1 summarizes the structural and functional changes within burn zones across different stages.

Table 1.

Structural and functional changes in burn zones during acute and late stages

| Burn Zone | 0–24 h | Acute Stage 24–48 h | 48–72 h | Late Stage 4–7 Days |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural changes | ||||

| Zone of coagulation | Collagen denaturation; cellular swelling and necrosis; thrombosis of blood vessels; area constant | Collagen coagulation; stable; area constant | Collagen coagulation; stable; area constant | Coagulative necrosis; area constant |

| Zone of stasis | Vascular stasis and ischemia; apoptotic cell death | Apoptotic cell death; vascular thrombosis; neutrophil accumulation; free radical injury | Apoptotic cell death; vascular necrosis | Apoptotic cell death; vascular necrosis; coagulative necrosis |

| Zone of hyperemia | Cytokines released; vasodilation; some damaged collagen recovers | Neutrophil accumulation; free radical injury | Inflammation | Inflammation resolves and tissue begins healing |

| Functional changes | ||||

| Zone of coagulation | Ischemia; loss of function | Loss of function of region | Loss of function of region | Loss of function of region |

| Zone of stasis | Stenosis of blood flow | Little change in depth; thrombosis of blood flow | Progressive tissue loss; ischemia | Ischemia; loss of function |

| Zone of hyperemia | Increased blood flow to region; edema | Edema decreases; inflammation | Inflammation | Tissue healing |

Light-Tissue Interaction and Depth of Optical Measurement

Optical imaging techniques, prominent in recent advancements, rely on understanding light-tissue interactions. Tissue optical properties, including refractive index (n), reduced scattering coefficient (μs/), and absorption coefficient (μa), govern light transport within tissue. Scattering describes light path deviations, while absorption reflects photon energy transfer to tissue molecules.

Optical imaging of skin involves collecting both scattered and specularly reflected photons. Specular reflection, originating from the tissue surface, lacks information about internal tissue composition and must be minimized for accurate imaging. Techniques like polarization and angle selection mitigate specular reflection.

Skin tissue optical properties are determined by its composition and layered structure. Key components influencing these properties include hemoglobin, melanin, water, and collagen. Hemoglobin, melanin, and water are primary absorbers, while collagen contributes significantly to scattering. Burn injuries alter the concentration and configuration of these molecules, making them detectable by optical techniques.

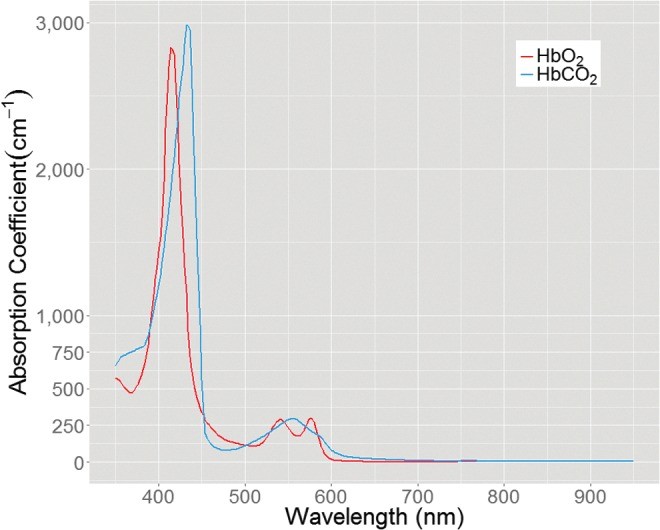

The depth of optical measurement is wavelength-dependent. Diffuse wide-field imaging approaches, such as MSI, collect reflectance spectra, revealing wavelength-dependent optical property variations. Hemoglobin absorption bands (Fig. 3) demonstrate that blue light penetrates less deeply than red light due to higher absorption. This principle dictates the tissue depth sampled by spectral imaging. Understanding this depth penetration is crucial for evaluating the capabilities of different optical instruments in assessing burn depth.

Figure 3.

Absorption spectrum of HbO2 and HbCO2, highlighting differences in light absorption at various wavelengths. HbO2, oxyhemoglobin; HbCO2, carboxyhemoglobin.

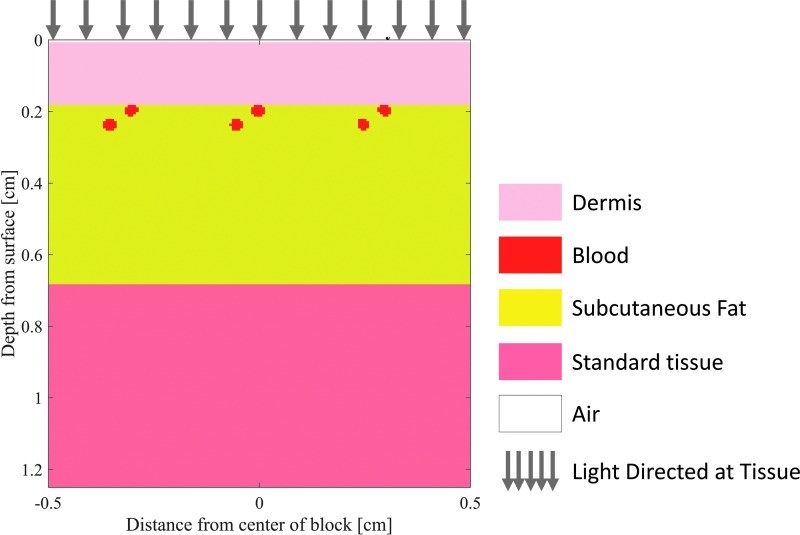

To illustrate the depth of tissue probed by visible and near-IR light, Monte Carlo simulations of light transport in tissue were performed. These simulations, using a layered skin tissue model (Fig. 4), generated sensitivity “clouds” (Fig. 5) depicting photon paths and average sampling depth by wavelength (Fig. 6). The results confirm deeper penetration of red light compared to blue light, demonstrating the wavelength dependence of sampling depth in skin and informing the evaluation of spectral imaging techniques for burn assessment.

Figure 4.

Layered skin tissue model designed for Monte Carlo simulations of diffuse light propagation, modified from the “mcxyz.c” simulation.

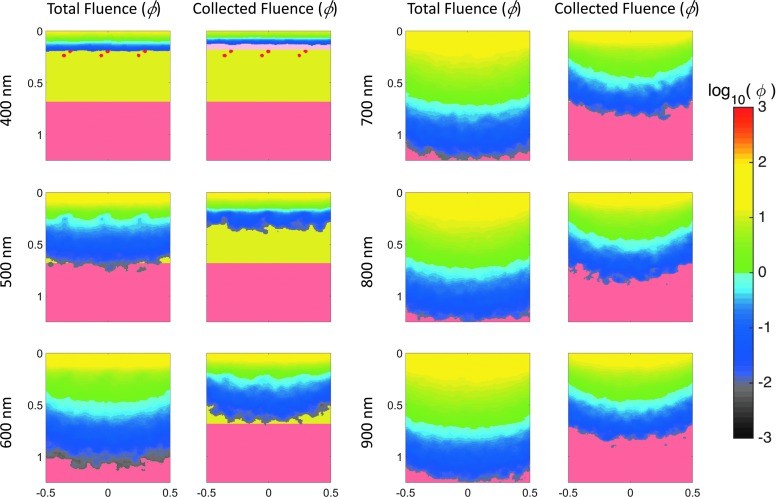

Figure 5.

Monte Carlo simulations of diffuse light directed at the layered tissue model in Figure 4. Left columns: Total fluence at select wavelengths. Right columns: Pathway of backscattered light collected by a sensor.

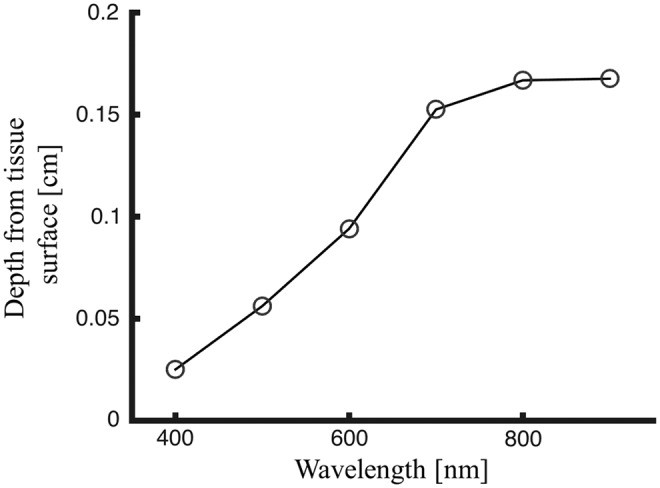

Figure 6.

Average sampled depth of collected fluence (average depth of backscattered light after entering the skin) as a function of wavelength, based on Monte Carlo simulation results.

Imaging Technologies for Assessing Burn Depth: A Comparative Evaluation

Technologies for burn wound assessment provide quantitative analyses of burn severity, healing potential, and infection status. These tools can be broadly categorized into imaging and nonimaging methods (Fig. 7). While nonimaging techniques offer improvements, this review focuses on imaging modalities. We will evaluate conventional and emerging imaging technologies for burn depth assessment, outlining their physical principles, clinical applications, and key characteristics (Table 2). This comparative evaluation is crucial for clinicians in Northern NJ and elsewhere to make informed decisions about technology adoption in their wound care practices. We conclude with an in-depth evaluation of MSI, highlighting its clinical potential and development pathway.

Figure 7.

Conceptual diagram categorizing burn assessment techniques into imaging and nonimaging modalities.

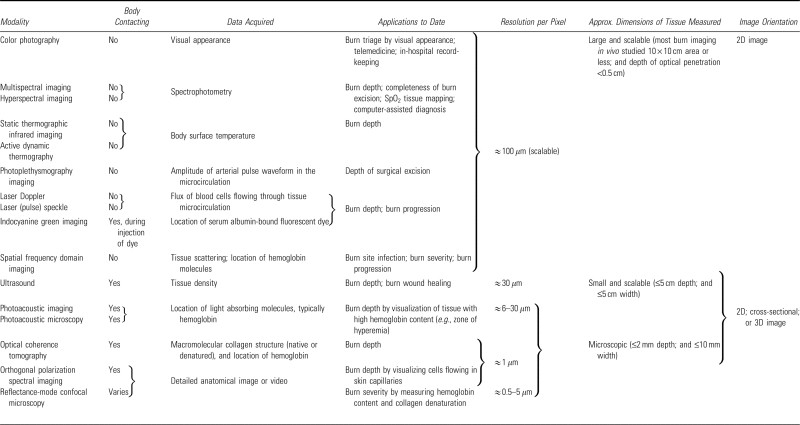

Table 2.

Characteristics of imaging modalities used in burn care and burn research

Conventional Imaging Modalities and Their Evaluation

Color Photography: Telemedicine and Limitations in Objective Evaluation

Color photography, a readily available and low-cost tool, is frequently used in telemedicine to enhance access to specialist burn expertise, especially in regions like Northern NJ where burn centers may be geographically distant. 15–21 Digital images can be easily shared for remote consultation and pre-arrival preparation at burn centers. However, color photography provides limited information beyond visual appearance, and its accuracy for burn assessment, even by experts, is debated.22 Factors like coloration and ambient lighting can significantly impact interpretation accuracy. While offering instantaneousness and portability, color photography cannot replace objective instrument-based evaluation for accurate wound assessment. Studies have shown that while helpful for expanding expert reach, it does not inherently improve assessment accuracy beyond the expert’s existing clinical judgment.27

Thermography: From Static to Active Dynamic Evaluation

Thermography, an early non-contact imaging technique, measures skin temperature gradients to assess perfusion. 28 Theoretically, deeper burns exhibit lower infrared radiation due to microvascular coagulation, making thermography potentially useful for burn depth estimation.29,30 Initial studies showed promising accuracy with static thermography.31 However, limitations in intratemporal and intrauser reliability due to evaporative cooling, wound granulation, and vascular depth variations across body locations 32,33 led to the development of active dynamic thermography (ADT). ADT measures tissue heat transfer conductance relative to surroundings, analyzing radiation trends over time to differentiate burn depths. 34,35 While ADT is still under evaluation, its dynamic approach offers potential improvements over static thermography in objective wound evaluation.

Indocyanine Green (ICG) Imaging: Vascular Perfusion Evaluation with Invasiveness Concerns

ICG videoangiography utilizes intravenously injected ICG dye, which fluoresces in the near-infrared range and binds to albumin in the blood, to assess vascular perfusion. 36 The fluorescence signal translates into perfusion maps, revealing vascular degeneration in burned tissue, a marker for burn severity.38 ICG imaging demonstrates accuracy in differentiating burn depths.39–41 Its early applicability post-injury is advantageous due to rapid vascular degradation.37 However, invasiveness due to dye injection and potential rare side effects 41, coupled with the recurring cost of ICG dye, are drawbacks. Furthermore, establishing universal wound severity thresholds remains challenging due to dermal vasculature variability. While valuable for perfusion evaluation, the invasiveness and cost necessitate careful evaluation in routine wound care settings.

Laser Doppler Imaging (LDI) and Laser Speckle Imaging (LSI): Microcirculation Evaluation and Emerging Alternatives

LDI is considered a promising technology for routine clinical burn depth determination, with commercially available devices in Europe and North America. 3 LDI uses laser light backscattered by moving red blood cells in microcirculation to measure blood flow (“flux”) at depths of 0.1 to 2.0 mm.42–44 Flux measurements are translated into color maps estimating healing time. LDI correlates strongly with histological assessment and the need for surgical excision, achieving accuracy up to 95% in studies.45,46 Despite high accuracy and safety (non-contact, non-radiation), LDI adoption has been slower than expected due to device expense, bulkiness, user-unfriendliness, and patient immobility requirements.36,47 Newer laser Doppler line scanners address data collection time limitations. However, LDI assessment can be affected by anemia, cellulitis, peripheral vascular disease, tissue topography, surface moisture, dressings, and ointments.48 Evaluation of LDI must consider these limitations alongside its high accuracy.

Laser speckle imaging (LSI), based on similar principles as LDI, addresses LDI’s limitations in cost, bulkiness, and motion sensitivity.49 LSI offers a lower-cost, faster acquisition alternative to LDI.50,51 Animal burn model studies 11,49,52 suggest promising clinical utility, with human trials anticipated.53,54 LSI represents a valuable advancement in microcirculation evaluation, potentially overcoming some of the practical barriers associated with LDI in wound care settings like those in Northern NJ.

Emerging Imaging Techniques and Their Evaluation

Reflectance-Mode Confocal Microscopy (RMCM): High-Resolution “Optical Biopsies”

Reflectance-mode confocal microscopy (RMCM) provides high-resolution “optical biopsies” for wound evaluation.36 RMCM uses near-infrared light and collects reflected light through a specialized aperture to image tissue structures at multiple focal planes up to ~350 μm depth.55 Tissue structures are contrasted by refractive index differences. RMCM generates 3D maps of injury areas by compiling these refraction differences.56 Theoretically, RMCM’s detailed microscopic structural information allows for precise burn depth and extent assessment, including visualization of dermal blood vessels, cells, epidermal-dermal junction, and white blood cells.57 However, RMCM application to human burn injuries is preliminary, with unknown clinical accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity.58 High cost, skin contact requirement, lengthy examination time (>10 minutes), small imaging area, and expert image interpretation are limitations.36 While offering detailed structural evaluation, RMCM faces practical challenges for routine wound care use.

Ultrasound: From Pulse-Echo to High-Frequency and Non-Contact Evaluation

Ultrasound technology for burn assessment has evolved from pulse-echo ultrasound for burn depth measurement 59 to B-mode ultrasonography for cross-sectional imaging.60 Initial clinical utility was limited, with marginal improvement over clinical assessment alone despite histological correlation.61,62 High-frequency ultrasonography offers improved resolution for dermal depth and wound healing assessment.63 While requiring skin contact, the enhanced resolution might justify this trade-off if it significantly improves burn diagnostics.64 Clinical utility of high-frequency ultrasound is still under evaluation.65

Traditional ultrasound’s contact requirement spurred investigation into non-contact ultrasonography.66 Further development to improve skin feature detection (sweat ducts, hair follicles) is needed for clinical translation.67 Non-contact ultrasound offers a promising avenue for safer, more convenient wound evaluation, particularly in burn care, but requires further evaluation and refinement.

Orthogonal Polarization Spectral Imaging (OPSI): Microscopic Perfusion Evaluation

Orthogonal polarization spectral imaging (OPSI) utilizes polarized lenses to minimize specular reflection and capture photons traversing into tissue, enabling microscopic blood perfusion imaging in vivo. OPSI directs polarized light at hemoglobin’s absorption peak (548 nm) and collects backscattered light. Milner et al. used OPSI to visualize microcirculation in burns, depicting red blood cells in capillaries in superficial burns and stagnant clot in larger vessels in deep burns.68 OPSI reveals microscopic details of dermal capillaries and blood flow dynamics for perfusion evaluation. However, its small field of view (1 × 1 mm) limits practical application for large wound areas.

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): High-Resolution Depth Evaluation and Polarization Sensitivity

Optical coherence tomography (OCT), widely used in ophthalmology, provides high-resolution cross-sectional (2D) or 3D tissue images, analogous to optical ultrasound. OCT measures the arrival times of backscattered light (typically infrared) by comparing it to a reference beam using Michelson Interferometry.69,70 This generates detailed images of tissue structures, including epidermis, dermis, and sweat glands, with 1–10 μm resolution and 1–2 mm imaging depth, similar to RMCM and OPSI. Small field of view and complex image interpretation are challenges for burn care application.

Polarization-sensitive OCT adds polarization state detection to depth measurement. Polarization measurements detect tissue birefringence, a property influenced by molecules like collagen. Polarization-sensitive OCT can non-invasively assess burn severity by quantifying collagen thermal denaturation through birefringence reduction.72,73 Reduced birefringence correlates with burn severity, offering a simpler metric for routine evaluation.

Efforts to extend OCT sampling depth include spectroscopic analysis of multiply scattered light. Matthews et al. developed a system reaching 9 mm depth with millimeter-scale resolution.74 This system provides deeper tissue anatomy imaging and spectroscopic analysis, but current 5-minute image acquisition times are a drawback for clinical use. OCT and its variations offer high-resolution depth and structural evaluation, but practical limitations in speed and field of view need to be addressed for broad wound care application.

Photoacoustic Imaging (PAI) and Photoacoustic Microscopy (PAM): Hybrid Imaging for Deeper Evaluation

Photoacoustic imaging (PAI) and photoacoustic microscopy (PAM) are hybrid techniques combining light and ultrasound. They utilize the photoacoustic effect, where laser light-induced ultrasonic waves are detected by an ultrasound probe. Variations in tissue optical absorption provide contrast, enabling visualization of different skin layers and constituents. PAM offers good resolution and deeper imaging depth (~1–5 mm) compared to OCT and OPSI.75 PAM is sensitive to hemostasis, hemorrhage, and hyperemia, making it useful for burn imaging.

In a pig burn model, PAM clearly visualized the zone of hyperemia, demonstrating its utility in determining thermally damaged tissue depth.75 PAI has been used to assess burn severity and healing, revealing detailed skin vasculature up to 3.0 mm depth.76 PAM image analysis requires knowledge of skin microanatomy for interpreting vascular changes indicative of burn severity. Future studies focusing on time-resolved hyperemic response evaluation with PAI would be beneficial. PAI’s sensitivity to absorbing molecules also enables edema monitoring by labeling albumin with Evans blue.77 PAI and PAM offer deeper tissue evaluation capabilities, but image interpretation complexity needs to be considered for clinical translation.

Photoplethysmography Imaging (PPGI): Blood Flow Evaluation for Debridement Guidance

Photoplethysmography imaging (PPGI) measures skin blood volume changes over time using optical methods. PPG signals, generated by light interaction with vascular tissue volume changes during the cardiac cycle, reflect arterial blood flow. PPGI uses digital cameras to capture millions of PPG signals across a large tissue area, translating them into arterial blood flow images.79,80,81 PPGI systems can detect signals up to one meter distance, with field of view and resolution comparable to digital cameras.

In a pig model, PPGI identified appropriate debridement points by differentiating PPG signal strength between viable and nonviable tissue, confirmed histologically.82 PPGI images revealed significant signal intensity differences between burned and viable tissue, suggesting its potential as a tool for guiding burn wound bed preparation. PPGI offers a non-contact method for blood flow evaluation and debridement guidance in wound care.

Multispectral Imaging (MSI) and Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI): Wide-Field Spectral Evaluation

Wide-field spectral imaging, including hyperspectral imaging (HSI) and multispectral imaging (MSI), analyzes reflected light spectra in the visible and near-infrared range (400–1,100 nm) from tissue surfaces. Both are spectrophotometry approaches collecting data simultaneously from an area. HSI provides richly sampled spectra (e.g., 1 nm intervals) advantageous for distinguishing similar compounds or identifying unknown absorbers. MSI uses fewer, selected wavelengths to characterize specific physiologically relevant components (hemoglobin saturation, blood volume, water, lipid). MSI systems typically offer higher image resolution, broader wavelength range, faster acquisition, and lower cost compared to HSI.83,84

Spectral imaging in burn care dates back to 1977 using filtered film cameras.85 Early MSI attempts used four wavelengths and relied on human image interpretation.85 Later, computational analysis was adopted. Afromowitz et al. found red, green, and near-IR light effective in predicting burn wound healing, achieving 86% accuracy in predicting healing within 21 days using red:near-IR and green:near-IR ratios.86,87 Machine learning algorithms further refined burn severity diagnosis using the same wavelengths.88 HSI in the near-IR range (650–1,050 nm) showed feasibility in differentiating burn depths in pig models.89–91 Increasingly complex predictive models and improved imaging technology enhance diffuse reflectance spectrum analysis.

MSI has also been applied to guide burn surgery excision. Studies demonstrated MSI’s ability to detect burn-injured tissue (~85% accuracy) and viable wound bed (~87% accuracy).82 Spectral differences between burn-injured and wound bed tissue are most significant at 515, 669, 750, and 972 nm, indicating compositional differences in blood, extracellular matrix, and water content.92 MSI offers wide-field, rapid spectral evaluation with promising accuracy for burn assessment and surgical guidance.

Spatial Frequency Domain Imaging (SFDI): Decoupling Absorption and Scattering for Depth-Resolved Evaluation

Spatial frequency domain imaging (SFDI) extends spectral imaging by using structured illumination patterns to achieve different tissue depth sensitivities. By projecting patterns with varying spatial frequencies and analyzing backscattered light images, SFDI quantifies tissue optical properties, including hemoglobin concentration, oxygen saturation (SpO2), and reduced scattering coefficient.93 SFDI decouples scattering and absorption properties, unlike MSI and HSI. SFDI also enables depth-dependent tomography through multi-spatial frequency analysis, offering information not obtainable without multi-length scale sampling. However, real-time image acquisition and processing are still under development.

SFDI-derived information is useful for assessing burn severity and burn progression in the first 3 days post-injury.11,94 SFDI can also detect infection in burn wounds.95 Nguyen et al. showed that scattering and absorption coefficients of infected burns diverged from non-infected burns 3 days post-S. aureus infection in a pig model.95 SFDI benefits include independent absorption and scattering quantification and a large scanning area (>10 × 10 cm). Ongoing efforts focus on real-time image acquisition and processing. SFDI provides advanced depth-resolved tissue evaluation capabilities.

Combination Systems: Synergistic Evaluation Approaches

Combining imaging techniques can leverage their complementary strengths to produce multi-parameter images. Ganapathy et al. developed a combined OCT and PSI system for burn assessment.54 This combination, analogous to Doppler ultrasound (anatomical information from OCT and perfusion data from PSI), achieved an average AUC of 0.85 in identifying burn depths in pig burns. Combining modalities can enhance diagnostic accuracy and provide a more comprehensive tissue evaluation.

Further Understanding of MSI: A Promising Tool for Wound Evaluation

Among the various technologies evaluated, MSI stands out as a highly promising modality for burn diagnosis due to its technical capabilities, environmental adaptability, and user-friendliness. MSI rapidly captures multiple independent tissue measurements, offering flexibility in diagnosing burn severity, identifying viable wound bed, and detecting hyperemia. Key advantages include large and scalable field of view, rapid data acquisition, accurate physiological parameter determination, and adaptability to diverse diagnoses across the burn care spectrum. For wound care facilities in Northern NJ and beyond, MSI presents a potentially transformative tool for enhancing diagnostic capabilities.

MSI Data Analysis: Oxygenation Mapping and Tissue Classification

MSI data analysis primarily focuses on either mapping microcirculation blood oxygen concentration or classifying tissue types within the image. Both approaches have significant clinical applications but employ different processing methods.

Images of Tissue Oxygenation: Quantitative Perfusion Evaluation

MSI can quantify hemoglobin volume fraction and relative oxygenated hemoglobin percentage.96,97 Mapping blood oxygen concentration from MSI data utilizes optical contrast principles similar to pulse oximetry. Pulse oximetry exploits the differential light absorption of oxyhemoglobin (HbO2) and deoxy- or carboxyhemoglobin (HbCO2). HbCO2 absorbs more red light (~650 nm) and slightly less near-IR light (~950 nm) compared to HbO2 due to oxygen-binding induced molecular configuration changes. MSI systems can measure red to near-IR absorption ratios to determine the relative proportion of oxygenated vs. deoxygenated hemoglobin. Unlike PPGI, which requires multiple seconds for pulse waveform calculation, MSI-based SpO2 calculation is instantaneous, eliminating blood volume variability associated with heartbeat cycles. MSI provides rapid, quantitative tissue oxygenation evaluation.

Tissue Classification by Diffuse Spectrum Analysis: Computer-Aided Diagnosis

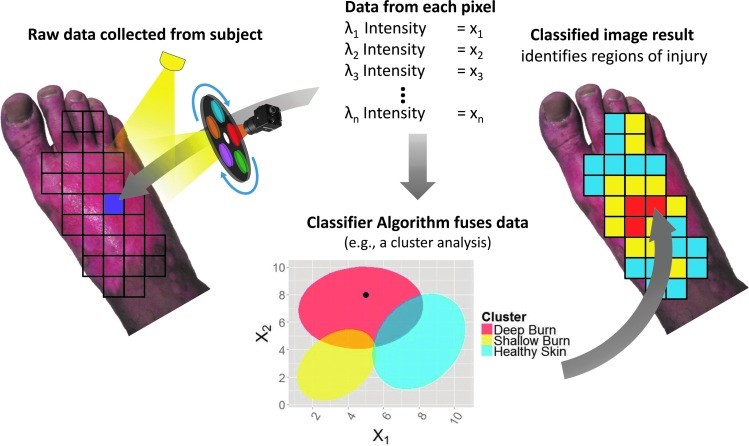

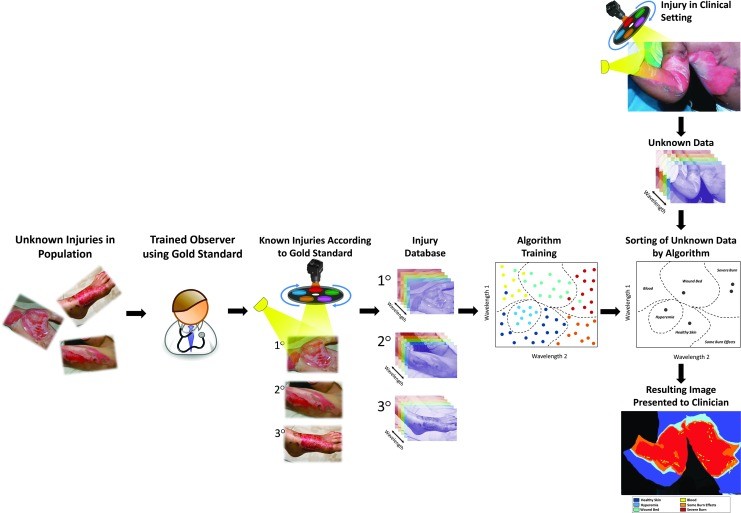

Another MSI data analysis method involves comparing tissue diffuse reflectance spectra to a reference library of known spectra. This technique classifies unknown spectra stochastically as tissue types or pathologies present in the reference library (Fig. 8). This approach is also known as computer-aided diagnosis, machine learning, or pattern recognition.98 Computer-aided diagnosis trains computer algorithms to recognize patterns in new data based on patterns in a pre-analyzed database.

Figure 8.

Illustration of applying a classification algorithm to MSI data from a single pixel. Multispectral data is collected, a low-resolution reflectance spectrum is obtained for each pixel, and the classifier identifies the tissue type at each pixel. MSI, multispectral imaging.

Developing an MSI system for burn depth diagnosis involves key steps (Fig. 9). Algorithm “training” is crucial, requiring a database of spectral patterns from varying burn depths. Supervised learning involves categorizing spectral data into burn severity classes using a ground truth reference (e.g., histology). The ground truth is essential for algorithm training and validation. Various mathematical techniques can be used for classification, and algorithm selection is based on computational evaluation. Classifier generation and validation are iterative processes, refining algorithm features until desired accuracy is achieved.

Figure 9.

Flowchart illustrating the development and application of an MSI-based machine learning model for burn wound classification. Horizontal arm: Steps for building a training database. Vertical arm: Clinical application of the trained algorithm for rapid patient diagnosis. MSI, multispectral imaging.

Recent MSI device development has focused on assisting burn surgeons in surgical excision adequacy determination. MSI captures multiple tissue measurements in ~2 seconds. An MSI system classified six different tissue types in a pig burn debridement model image. Clinically relevant burn tissues, including partial-thickness burns and hyperemia, exhibit unique reflectance spectra. Time since injury significantly impacts burn reflectance spectra.92 Machine learning applied to tissue spectral measurements yielded favorable validation results, achieving 87% average accuracy in classifying tissues relevant to wound bed preparedness in a burn surgery animal model.82 MSI combined with machine learning offers a powerful approach for objective wound tissue classification and computer-aided diagnosis, holding significant promise for wound care in Northern NJ and beyond.

Summary and Future Directions in Wound Evaluation Technologies

Numerous technologies have demonstrated success in burn assessment, but the selection of appropriate imaging technology for wound care augmentation remains challenging. Tissue area imaged varies, with some devices scanning large areas (>10 × 10 cm) and others producing microscopic images. Ultrasound offers the greatest imaging depth (~5 cm), while optical methods penetrate up to 0.35 cm, depending on wavelength.99 Technologies like thermography, MSI, and LSI, capable of rapid large-area imaging, are suitable for initial burn assessment and triage. For presurgical planning, technologies like OCT, OPSI, PAM, or ultrasound, offering detailed spot-checking capabilities, may be more useful.

While superior alternatives to clinical judgment and photography exist, user-friendliness remains a crucial factor for adoption. Burn care providers emphasize the need for improved human factors and user-friendly designs in commercial burn care devices.3 Non-contact methods are safer and more clinically sustainable. Portability, accessibility, accuracy, and cost also significantly influence technology acceptance.

As burn care advances, improved wound evaluation is crucial for managing increasingly severe burn injuries. While accurate burn depth assessment is critical, other applications of imaging technologies in wound care are equally important, including early infection identification, guiding excision depth to minimize skin graft area and scarring, and enhancing non-specialist care provider effectiveness. Emerging fluorescence imaging for wound infection detection 101 and Terahertz imaging for through-dressing burn assessment 102 represent further advancements.

Predicting burn progression and tissue conversion to necrosis is a key future direction for burn depth imaging. Technologies detecting features in the zone of stasis (inflammation, edema, ischemia) could be valuable for predicting burn conversion. Correlating imaging measurements with these pathological processes over time will be a major focus in future imaging studies, aiding in faster surgical decisions and maximizing tissue sparing. Continued evaluation and development of these technologies will be essential for advancing wound care practices in facilities serving regions like Northern NJ and globally.

Take-Home Messages.

- • Non-specialist burn wound assessments have limited accuracy (60% for depth, 51% for size).

- • Expert clinical judgment accuracy in burn depth assessment is 70–80%.

- • Imaging technologies demonstrate higher burn depth assessment accuracy (>80%) than clinical judgment alone.

- • Clinical adoption of burn diagnostics requires ease-of-use, rapid large-area assessment, and high accuracy.

- • Optical methods dominate recent burn imaging advancements, offering sufficient skin penetration for burn severity and healing assessment.

- • Imaging techniques assess either anatomical or physiological tissue parameters, necessitating knowledge for appropriate technology selection and result interpretation.

- • Preclinical and clinical studies support imaging technologies for burn depth assessment, infection monitoring, and wound bed preparedness diagnosis.

- • Thermography and LSI are suitable for initial burn assessment and triage due to rapid large-area imaging capabilities.

- • Ultrasound and optical microscopy techniques are more useful for presurgical planning and detailed spot-checking.

- • MSI is an emerging technique providing wide-field images depicting burn presence and severity, showing promising preclinical accuracy.

- • Clinical trials are needed to build reliable reference libraries for MSI-based computer-assisted burn diagnosis in routine care.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

μa absorption coefficient

μs/ scattering coefficient

2D two dimensional

3D three dimensional

ADT active dynamic thermography

AUC area under the receiver-operator characteristic curve

EB Evans blue

HbCO2 carboxyhemoglobin

HbO2 oxyhemoglobin

HSI hyperspectral imaging

ICG indocyanine green

LDI laser Doppler imaging

LSI laser speckle imaging

MRSA methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

MSI multispectral imaging

n refractive index

OCT optical coherence tomography

OPSI orthogonal polarization spectral imaging

PAI photoacoustic imaging

PAM photoacoustic microscopy

PPGI photoplethysmography imaging

RMCM reflectance-mode confocal microscopy

SFDI spatial frequency domain imaging

SpO2 oxygen saturation

TBSA total body surface area

W watts

Acknowledgments and Funding Sources

We sincerely thank Professor James H. Holmes, MD of Wake Forest, and Professor Steven E. Wolf, MD of UT Southwestern Medical Center for their detailed discussions about the burn care workflow. This work was supported, in part, by the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA).

Author Disclosure and Ghostwriting

J.E. Thatcher and J.M. DiMaio receive salary from Spectral MD, Inc. and have ownership in Spectral MD, Inc. through stock. J.J. Squiers, D.R. King, Y. Lu, and E.W. Selke receive salary from Spectral MD, Inc.

About the Authors

Jeffrey E. Thatcher, PhD, is the Chief Scientist at Spectral MD, Inc. where he oversees technology and applications research for medical imaging systems. His interests are in translational research of noninvasive imaging for wound care. His work in burn imaging was recognized by the 2015 Burke/Yannas award for original research in biomedical engineering from the American Burn Association. John J. Squiers, BSE, focuses on clinical applications and clinical trial design as Clinical Specialist at Spectral MD, Inc. Stephen C. Kanick, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Engineering at Dartmouth where his research focuses on developing biophotonics for better methods to diagnose and treat cancer. Darlene R. King is a biomedical engineer at Spectral MD, Inc. Yang Lu, PhD, is an algorithm development engineer at Spectral MD, Inc. Yulin Wang, PhD, is a human factors engineer at Spectral MD, Inc. Rachit Mohan is a student at Columbia University and recently completed an internship with Spectral MD, Inc. Eric W. Sellke, BS, is a biomedical engineer at Spectral MD, Inc. J. Michael DiMaio, MD, is the founder and CEO of Spectral MD, Inc. He received his MD from the University of Miami and completed his thoracic surgery residency at Duke. He serves as the Director of Postgraduate Education and Publications at Baylor Research Institute.