Introduction

In the pursuit of minimizing medication errors and bolstering patient safety, barcode medication administration (BCMA) has emerged as a pivotal technology in healthcare settings. BCMA systems are designed to verify medication identity, dosage, and patient identity right at the point of care, significantly reducing the risks associated with traditional medication administration processes. Integrating Barcode Medication Scanning At The Point Of Care into healthcare workflows represents a proactive step towards creating a safer environment for patients and streamlining processes for healthcare providers. This article delves into the impact of BCMA on nursing workflows and patient safety, drawing insights from a detailed comparative study conducted in a UK hospital.

The implementation of BCMA typically involves scanning a patient’s unique barcode, usually on their wristband, and the barcode on the medication before administration. This process ensures that the right medication is given to the right patient in the correct dose, at the right time, and via the right route – the fundamental ‘rights’ of medication administration. BCMA systems are frequently integrated with electronic prescribing and medication administration (ePMA) systems, creating a comprehensive digital medication management ecosystem. The reported benefits of BCMA are numerous, primarily centered around the reduction of medication administration errors and improvements in patient identification. Studies have shown a significant decrease in both the incidence and severity of medication errors following the adoption of BCMA [2,3,4,5]. Furthermore, BCMA has been credited with dramatically increasing the percentage of patients for whom identity is actively checked before medication administration [6].

However, the effectiveness of barcode medication scanning at the point of care is not solely dependent on technology. Human factors and workflow integration play crucial roles. Concerns have been raised that if BCMA implementation disrupts or hinders nurses’ workflows, it may lead to workarounds that diminish its intended benefits. These workarounds can include bypassing essential scanning steps or finding ways to circumvent the system for perceived efficiency gains [8,9]. Therefore, understanding the real-world impact of BCMA on nursing activity and workflow is critical. While previous research has explored the effects of BCMA compared to paper-based systems, fewer studies have examined its impact when added to existing ePMA systems—a common scenario in hospitals today [1]. Moreover, nurses’ perceptions of BCMA are varied, with some reporting increased time spent on medication administration and others acknowledging its importance for medication verification [13,14,15]. These conflicting viewpoints underscore the need for more research to evaluate the practical implications of barcode medication scanning at the point of care in contemporary healthcare settings.

This article aims to assess the impact of implementing barcode medication scanning at the point of care in a UK hospital already utilizing an ePMA system. The objectives were to compare medication administration processes on wards with and without BCMA, focusing on:

- The duration of drug administration rounds.

- The timeliness of medication dose administration.

- The rate of active patient identification by nurses.

- The rate of active medication verification by nurses (BCMA ward only).

- Nursing workflow patterns within the ward.

Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting the Stage

The study was carried out across two surgical wards in a large acute hospital in London. Data collection occurred on a gastrointestinal surgery ward prior to BCMA implementation and, subsequently, on a vascular surgery ward four days post-BCMA implementation. The wards were structurally identical, each accommodating 24 beds distributed across four bays and four side rooms.

During medication rounds, nurses administered medications from ward stock, patient-specific dispensed medications, and patients’ own medications brought from home. Patient-specific and home medications were typically stored at the bedside, while ward stock was kept in the medication room or in lockable cabinets on mobile computer workstations known as COWs (computers on wheels). On the non-BCMA ward, some COWs had medication cabinets that were accessible to all staff and not consistently available during drug rounds. In contrast, the BCMA ward was equipped with designated COWs for drug rounds, each fitted with a larger medication cabinet, alongside general-use COWs without cabinets. Nurses used the ePMA system on the COWs to access medication schedules and record administrations. Before BCMA, each dose administration required an individual electronic signature. Drug rounds were scheduled at 8 am, 12 pm, 2 pm, 6 pm, and 10 pm, aligning with typical medication administration times. Each nurse was responsible for medication administration in a bay of five beds and potentially a side room.

Both the ePMA and BCMA systems were components of the Cerner Millennium suite [17]. Post-BCMA implementation, nurses used barcode scanners connected to designated COWs during medication rounds. After accessing a patient’s medication administration record, the system prompted a scan of the patient’s wristband for identity verification. Upon successful scan, the patient’s medication list appeared, and nurses were required to scan each medication barcode for system validation. Once all medications for a patient were administered and scanned, nurses could provide a single electronic signature for the entire patient’s medication administration, instead of signing each dose individually. The system was designed to generate a warning if either the patient or medication barcode scan did not match the expected details, prompting the nurse to rectify the discrepancy or provide a justification for overriding the alert.

2.2. Study Design and Data Collection Methodology

This study employed a comparative design using direct observation to gather data during the 8 am drug rounds. Data were collected over ten consecutive weekdays in November 2019 on the non-BCMA ward and then for ten weekdays in December 2019 on the BCMA ward. To maintain consistency, bay “H” was randomly selected for daily observation. Nurses responsible for this bay during each drug round were approached for consent to be observed. A pharmacy student conducted the observations with the aim of minimal disruption. The study was approved as a service evaluation, and NHS ethics approval was deemed unnecessary. Data were collected based on the outcome measures listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Outcome measures and data collection methods.

| Outcome Measure | Method |

|---|---|

| Drug administration round duration | Time recorded from opening the electronic record for the first patient to the final medication dose administration recording for the last patient. This included all activities and interruptions during the round. Patient count, doses due, and doses administered were also recorded. |

| Timeliness of medication administration | Scheduled and actual administration times were recorded for each directly observed dose. ‘When required’ medications were excluded. The time difference between scheduled and administered times was calculated for each dose. |

| Active positive patient identification activity | Non-BCMA ward: Nurse confirmation of at least two patient identifiers (name, date of birth) via wristband check or verbal confirmation. BCMA ward: Wristband barcode scan or two-identifier confirmation. Method used was recorded. |

| Active positive medication dose verification activity | BCMA ward only: Recording of medication barcode scanning for each dose, reasons for non-scanning, and observed workarounds. |

Additionally, on eight drug rounds per ward, spaghetti diagrams [18,19] were created to map nurse walking patterns. These diagrams detailed the ward layout and the nurse’s path from the start to the end of the drug round. The first two days on each ward were used to establish the floorplan before spaghetti diagrams were constructed for the subsequent eight days.

Quantitative data were compiled in Excel. After reviewing for skewness, mean drug round duration was calculated for each ward using an unpaired t-test to determine statistical significance. Secondary analyses included mean time per patient and mean time per dose. Timeliness was assessed by calculating the mean time difference between scheduled and administered times. Patient identification rates were compared using a chi-square test. On the BCMA ward, medication verification rates were also calculated. Spaghetti diagrams were visually analyzed to identify differences in workflow and walking patterns.

3. Results

Over the study period, ten drug rounds were observed on each ward. The number of patients receiving medication varied from three to six per round. The average number of doses administered was 17 (range 7–25) on the non-BCMA ward and 29 (range 21–38) on the BCMA ward. Seven nurses were observed on the non-BCMA ward and eight on the BCMA ward.

3.1. Drug Administration Round Duration Findings

The average drug round duration was 67.8 minutes (range 27–98 minutes) on the non-BCMA ward and 68.0 minutes (range 48–99 minutes) on the BCMA ward (p = 0.98; t-test). Significant variability in drug round duration was noted, particularly on the non-BCMA ward, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Drug round duration comparison over time between the non-BCMA and BCMA study wards.

Analyzing the components of drug round duration, the mean time per patient was 14.1 minutes (range 9.0–19.6 minutes) on the non-BCMA ward and 16.0 minutes (range 11.6–20.0 minutes) on the BCMA ward (p = 0.17; t-test). However, the mean time per dose showed a significant difference, with 4.2 minutes (range 3.3–5.5 minutes) on the non-BCMA ward and 2.3 minutes (range 1.8–3.2 minutes) on the BCMA ward (p < 0.001; t-test).

3.2. Timeliness of Medication Administration

On the non-BCMA ward, out of 185 scheduled medication doses, 165 (89%) were administered. On the BCMA ward, 294 (81%) of 363 scheduled doses were administered. Unadministered doses were due to patient refusal, medication review requirements, or unavailability of the medication on the ward. The mean time difference between scheduled and administered times was 60.3 minutes on the non-BCMA ward and 67.5 minutes on the BCMA ward. Medication administration appeared to be more timely on the non-BCMA ward (p = 0.007; t-test). Notably, drug rounds on the BCMA ward often started later, with seven of ten rounds beginning after 8:30 am, compared to only one on the non-BCMA ward.

3.3. Active Positive Patient Identification Improvements

Nurses administered medication to 47 patients on the non-BCMA ward, with positive patient identification checks conducted for 35 (74%) of them. In stark contrast, on the BCMA ward, all 43 patients (100%) receiving medication had their identification checked, representing a significant increase with BCMA implementation (p = 0.001; chi-square test). On the non-BCMA ward, all positive identifications involved manual wristband checks. On the BCMA ward, BCMA scanning was used for patient identification in 40 cases (93%), supplemented by manual checks in 13 cases (30%). In three instances (7%) involving side room patients where COWs were restricted due to infection control, nurses scanned barcode stickers from patient notes instead of wristbands, always accompanied by a manual wristband check.

3.4. Active Positive Medication Verification Rates

On the BCMA ward, the majority (255 of 294; 87%) of administered doses had scannable barcodes. Non-scannable medications included repackaged patient-owned drugs and individually stored insulin pens without their original packaging. While most medications had barcodes, some, like nutritional supplements and vitamins, were not recognized by the BCMA system, requiring manual signing for administration. Of the 294 doses administered, 243 (83%) were scanned before administration, accounting for 95% of scannable doses. Only 12 potentially scannable doses were not scanned, 11 of which were subcutaneous enoxaparin doses prepared in the medicines room. Although the boxes were scannable, most nurses administering enoxaparin chose to leave the boxes in the medicines room.

BCMA system warnings occurred in 14 cases (6% of scanned doses). One (0.4% of scanned doses) was a medication error where the nurse initially selected the wrong formulation (co-amoxiclav tablets instead of injection), which was corrected upon the system warning. The remaining 13 warnings included issues such as doses not identifiable by barcode, variable doses requiring manual entry, half-tablet doses flagged as potential overdoses, and doses administered too early and overridden. In each warning case, nurses took corrective actions, either manually amending the record or providing override justifications.

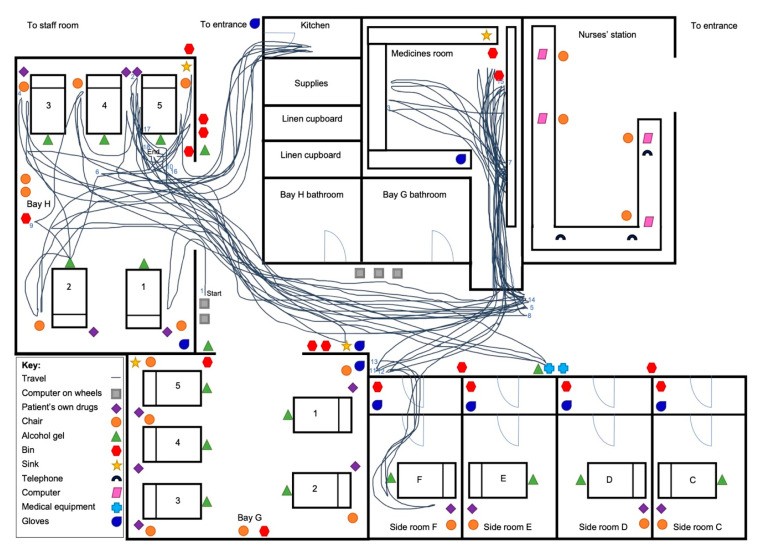

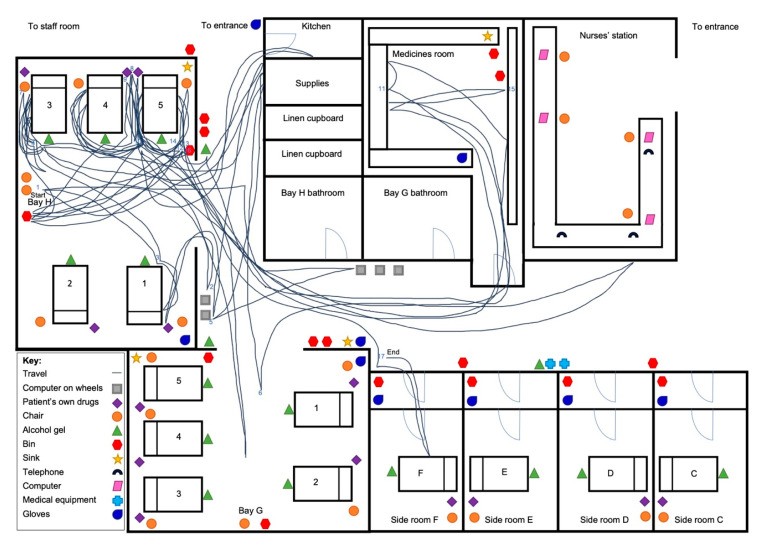

3.5. Nurse Workflow and Ward Movement Patterns

Spaghetti diagrams provided visual insights into nurse movement patterns. Figure 2 shows a representative diagram from the non-BCMA ward, illustrating frequent movement between patient beds and the medicines room. This pattern was consistent in several other diagrams from the non-BCMA ward. Conversely, Figure 3 from the BCMA ward consistently showed reduced movement to areas like the medicines room, with most movement concentrated between patient beds. This indicates a more streamlined workflow with barcode medication scanning at the point of care, reducing the need for nurses to repeatedly visit the medicines room during drug rounds.

Figure 2. Nurse walking pattern on a non-BCMA ward during a drug round.

Figure 3. Nurse walking pattern on a BCMA ward during a drug round.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Observations on BCMA Impact

The findings from this study indicate that the introduction of barcode medication scanning at the point of care does not significantly alter the overall duration of drug rounds. However, this comparison is nuanced by the fact that more doses were administered per patient on the BCMA ward. The reduced time per dose on the BCMA ward suggests an increased efficiency in medication administration, enabling nurses to manage a higher volume of doses within a similar timeframe. While the data indicated a potential decrease in the timeliness of medication administration with BCMA, this may be attributed to later drug round start times on the BCMA ward rather than the system itself. Had the start times been consistent, it is plausible that no significant difference in timeliness would have been observed. The reduced time per dose suggests that BCMA has the potential to improve timeliness by streamlining processes and minimizing travel to the medicines room for dose preparation and retrieval.

A significant outcome of implementing barcode medication scanning at the point of care is the achievement of 100% patient identification checks. The BCMA system mandates patient barcode scanning before medication administration, ensuring a consistent patient identification process. However, the observed workaround of scanning barcode stickers from patient notes for side room patients, performed by multiple nurses, raises a potential concern. While intended to overcome technological limitations in side rooms, this practice could inadvertently elevate the risk of wrong-patient errors if not carefully managed.

The high medication scan rate observed is a positive indicator of BCMA system adherence among nurses. It demonstrates a general acceptance and utilization of barcode medication scanning at the point of care as part of their routine medication administration process. However, the inconsistent scanning of enoxaparin boxes suggests a need for better education and understanding among nurses regarding the system’s capabilities and the importance of scanning all scannable medications to maximize safety benefits. Beyond enhancing patient identification, barcode medication scanning at the point of care also demonstrated its potential to prevent medication errors. In one observed instance, the system alerted a nurse to an incorrect medication formulation, allowing for timely correction before it reached the patient, highlighting a tangible patient safety benefit.

4.2. Contextualizing Findings with Prior Research

This study uniquely examined the impact of BCMA as an addition to an existing ePMA system, unlike many previous studies that compared BCMA to paper-based systems [10,11]. This difference in context limits direct comparisons with earlier research. Contrary to findings from a US study that reported increased total medication administration time with BCMA [12], this study did not find an increase in drug round duration. The US study attributed the increased time to more time spent on direct patient care during medication rounds [12], a factor not measured in our study. The workaround involving scanning barcode stickers instead of wristbands, observed in this study, has also been reported in previous research [8,9], suggesting it is a recurring issue across different healthcare settings implementing barcode medication scanning at the point of care.

4.3. Practical Interpretations and Implications

Barcode medication scanning at the point of care appears to standardize the medication administration process, largely due to the use of designated medication cabinets on COWs, which streamlines workflow by centralizing medication access. Additionally, BCMA has the potential to reduce medication documentation time by enabling batch signing for all doses administered to a patient, rather than individual dose signing. Despite these efficiencies, the overall drug round duration remained unchanged in this study. This could be attributed to the increased number of doses administered on the BCMA ward and the time required for barcode scanning, particularly patient wristbands, which nurses sometimes found cumbersome due to COW maneuverability and scanner aiming challenges. As barcode medication scanning at the point of care becomes more prevalent in inpatient settings [1], these findings underscore the importance of user-centered design improvements, such as wireless scanning devices that can be easily used in all patient care areas, including side rooms.

The enhanced rates of patient identification and medication verification achieved through barcode medication scanning at the point of care present significant advantages for patient safety. However, to further optimize medication verification, it is crucial to expand the database of barcoded medications and improve nurses’ understanding of which medications are scannable. This may be achieved through extended system use, ongoing training, and feedback mechanisms. Furthermore, there is a potential risk of complacency with BCMA, as suggested by observations of some nurses potentially overlooking manual checks like expiry date verification, assuming the BCMA system covers all safety checks. Therefore, comprehensive training should emphasize BCMA as an adjunct to, not a replacement for, clinical judgment and thorough medication safety practices.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

This study is among the few to investigate the impact of barcode medication scanning at the point of care on nursing workflow in a real-world hospital setting, providing valuable insights for future research and practice. A key strength is the use of a single observer for data collection, ensuring consistency in observations and workflow assessments. Direct observation methodology also overcomes the limitations inherent in self-reported data.

However, the study design, comparing two different wards rather than a before-and-after comparison on the same ward, introduces limitations. While the wards were similar, differences existed, potentially introducing bias. Variations in drug round start times, different COW models, and significant differences in doses administered per round and per patient could have influenced drug round duration and timeliness findings. Unaccounted practice differences between wards cannot be excluded. Data collection shortly after BCMA implementation on the BCMA ward means that staff may not have been fully proficient with the system, potentially affecting results. The study’s relatively small scale and single-center nature may limit the generalizability of findings to other institutions with different medication administration practices and BCMA systems. Finally, the Hawthorne effect—the influence of observation on behavior—cannot be ruled out, although this would have been present in both study wards.

4.5. Directions for Future Research

Future research should ideally employ a pre- and post-BCMA implementation design on the same wards to allow for direct workflow comparisons. Observing drug rounds at different times of the day would provide a more comprehensive understanding of BCMA’s impact across various shifts and medication administration schedules. Larger-scale, longer-duration studies, conducted several months post-BCMA implementation, are needed to capture steady-state practice and long-term effects. Employing time-motion or work sampling methodologies could offer quantitative data on time allocation across different nursing activities, further elucidating the nuanced impacts of barcode medication scanning at the point of care on nursing workflow and efficiency.

5. Conclusions

This study suggests that barcode medication scanning at the point of care does not negatively impact the time nurses spend administering medications. While initial data indicated potentially reduced medication administration timeliness with BCMA, this finding requires cautious interpretation and further investigation, ideally through pre- and post-implementation studies on the same wards. Overall, BCMA appears to promote greater consistency in medication administration workflows. The significant improvement in active patient identification and the high rate of medication verification achieved through barcode scanning represent substantial potential benefits for enhancing patient safety at the point of care.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude to the nursing staff of both participating wards for their cooperation and participation in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.D.F.; methodology, S.B. and B.D.F.; formal analysis, S.B. and B.D.F.; investigation, S.B.; data curation, S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.; writing—review and editing, B.D.F.; supervision, B.D.F.; project administration, S.B. and B.D.F. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant funding. B.D.F.’s work is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Imperial Patient Safety Translational Research Centre and the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Healthcare Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance at Imperial College London, in partnership with Public Health England (PHE). The views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NHS, PHE, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

[1] Cornish, J.; Ahuja, J.; Keepanasseril, A.; Clark, C.; Grey, N.H.; Garrett, K.; Teoh, Z.; Herwadkar, A.; Patel, M.J. Implementation of Electronic Prescribing and Medicines Administration Systems in NHS Acute Hospitals in England: A Survey Study. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 148.

[2] Poon, E.G.; Keohane, C.A.; Yoon, C.S.; Ditmore, M.; Bane, A.; Levtzion-Korach, O.; Moniz, T.; Rothschild, J.M.; Kachalia, A.; Hayes, J.; et al. Effect of Bar-Code Technology for Medication Administration on Medication Errors and Unsafe Conditions. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 152, 729–738.

[3] Shane, R.; Toohey, S.L.; Valenta, S. Impact of Barcode Medication Administration Technology on Patient Safety. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2010, 67, 1857–1862.

[4] Trbovich, P.L.; Prakash, V.; Stewart, S.; Leslie, K.; Willan, A.R.; Baker, G.R.; Easty, A.C.; Straus, S.E. Bar-Code Medication Administration: Evaluating Safety and Workflow. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2010, 182, E108–E116.

[5] Weber, R.J.; Westrick, S.C.; Coley, K.C.; Feinstein, D.L.; Esper, S.A.; Kessler, R. Impact of Bar-Code Assisted Medication Administration Technology on Medication Error Rates and Nurse Job Satisfaction in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 17, 403–412.

[6] Abdolkhani, R.; Kelk, G.; Lingard, L.; Etchells, E.E.; Jabbari, M.; Baker, J.A. Barcode Medication Administration Technology: A Systematic Review of Implementation Challenges. Healthc. Q. 2015, 18, 10–21.

[7] vanOnkelen-Felix, T.M.; Vermeulen, K.M.; van Dulmen, S.; Kaljouw, M.J. Potential and Limitations of Barcode-Assisted Medication Administration in the Reduction of Medication Administration Errors: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2012, 19, 96–104.

[8] Bowman, S. Barcode Medication Administration Workarounds: Description and Analysis. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2012, 69, 415–424.

[9] Cai, H.; Harrison, M.I.; Hayes, T.L.; Szerencsy, A.; Abraham, I.; Barker, K.N. Bar-Code Medication Administration System: A Qualitative Analysis of Workarounds. J. Healthc. Qual. 2012, 34, 49–57.

[10] Franklin, B.D.; O’Grady, K.; Donyai, P.; Jacklin, A.; Barber, N. The Impact of a Closed-Loop Electronic Prescribing and Administration System on Workload and Workflow for Nurses and Pharmacists. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2007, 14, 529–542.

[11] Hawkins, R.E.; Ozog, D.M.; Wermeling, D.P.; Brown, J.D. Evaluation of the Impact of Bar Code Medication Administration on the Time Nurses Spend on Medication-Related Tasks. J. Healthc. Qual. 2008, 30, 4–12.

[12] Tucker, A.L.; Spear, S.J. Operational Failures and Interruptions in Hospital Nursing. Health Serv. Res. 2006, 41, 643–662.

[13] Anderson, P.; Townsend, T.;蘸inan, E.;于, P.; Bates, D.W.; Gupta, S. Bar-Code Medication Administration Technology: Perceived Benefits and Barriers. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2010, 67, 1849–1856.

[14] Johnson, K.B.;濡al, S.; Vemulapalli, B.; Payne, T.H.; Bloomrosen, M.; Brown, S.H.; FitzHenry, F.; Hammond, W.E.; Hernandez, J.E.; Hoey, P.; et al. Consumer Perceptions of Electronic Health Records: A Report from the AHIC Consumer Empowerment Workgroup. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2008, 15, 432–440.

[15] Kim, T.Y.; Lee, Y.R.; Kim, J.A.; Lee, E.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, M.J.; Kang, E.Y. Nurses’ Perceptions of Barcode Medication Administration Systems: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 61, 19–26.

[16] Wu, W.Y.; Lai, H.Y.; Tung, T.H.; Lin, Y.P.; Lee, C.H.; Chang, C.C. Nurses’ Perceptions of Barcode Medication Administration Systems in Taiwan: A Qualitative Study. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 40, 1–6.

[17] Cerner Millennium. Available online: https://www.cerner.com/solutions/ephm (accessed on 15 March 2024).

[18] Holden, R.J.; Carayon, P.; Hoonakker, P.L.; Schoeman, J.P. Spaghetti Plots, Storyboards, and Time-Motion Studies: Visualizing Work in Healthcare. Ergonomics 2008, 51, 135–159.

[19] Kim, M.J.; Stichler, J.F.; Ecoff, L.; Brown, K.J.; Boyer, N.; Johnson, J.L. Using Spaghetti Diagrams to Visualize Workflow in the Emergency Department. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2015, 41, 297–302.

[20] Sedgwick, P.; Greenwood, N. Understanding the Hawthorne Effect. BMJ 2015, 351, h6492.